The Olympian Fighting for Her Right to Run In her memoir, Caster Semenya details how she has coped with being banned from the sport she loves.How do they accept men to compete in women's sport but reject a real woman from competing in women's sport? That's Hypocrisy of the Highest Order

When Caster Semenya was 12 years old, she introduced herself to her cousin’s friends as Thabiso, a boy’s name. “I could tell they thought I was a boy, so I figured I would go along with it,” she writes in her new memoir, The Race to Be Myself. “I was swimming without a shirt on, and I had no boobs. I looked tough like they did. My voice sounded like theirs, too.” The little white lie was corrected once school started and, wearing a dress, she introduced herself to the class as Caster. It was perhaps the first — but definitely not the last — time she realized people could be confused about her gender.

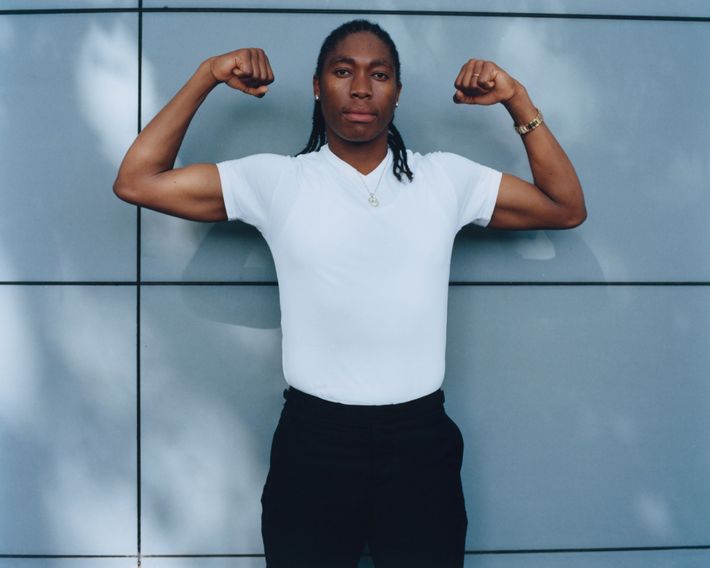

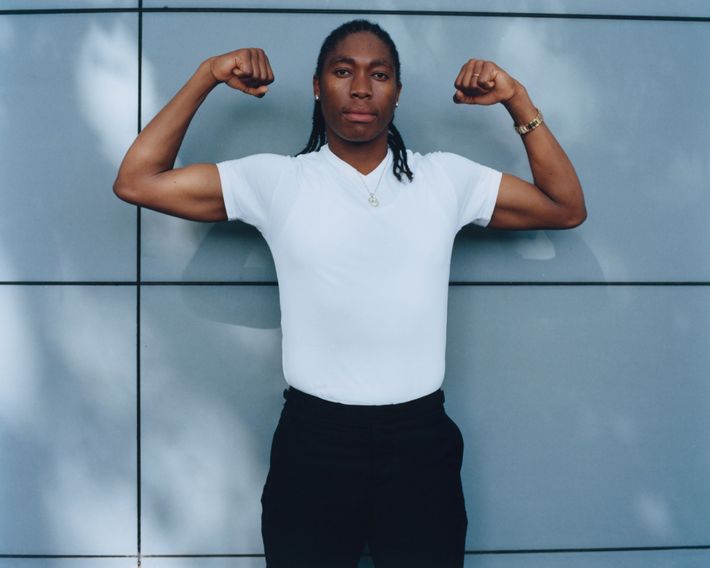

Today, on a summer afternoon in South London, the middle-distance runner laughs over that childhood memory. Tall, muscular, and slim, she presents herself exactly as you would expect a professional athlete to look on a day off: dressed in a white Nike hat, a black “Just Do It” top, checked shorts, and sneakers (one black, one white). She also wears a confident smile, diamanté earrings, and the simple braided hairstyle for which she is known. But the 32-year-old’s laughter covers up the tense reality of what it was really like to be mistaken for a boy in her childhood and adulthood. Her appearance, her deep voice, and the spectacular athletic performances that earned her two Olympic gold medals have also significantly stunted her career.

Semenya meets me in the outdoor seating area of a greasy spoon on the corner of a busy road; the noisy cars soon become a distraction, and we agree to move elsewhere. She walks with a leisurely gait, the kind often attributed to those, like herself, who grew up in the warm countryside. While it is unclear whether passersby recognize the athlete, they turn their heads at her strong presence and resonant voice. She does not seem to notice this as we make our way to our next spot, a quaint, traditional Irish pub called the Pineapple, where she settles into a sofa in the corner, sitting with immaculate posture and her legs widely spread. Above her, a cricket match plays on a large television as she discusses her upcoming book, a first-person account of her life from her time growing up in Limpopo, a province in northeastern South Africa, to the present day and of battling the ongoing prejudices that have seen every aspect of that life picked apart. Her memoir details her enduring fight to run.

“Over the years, I’ve let people do a lot of talking, but they’re not talking about the real issue here,” she says matter-of-factly, sipping on a glass of water. For Semenya, the real problem has always been that she is a woman. She was assigned female at birth, raised as a girl, and has never considered herself anything else. Yet for the past four years, she has been prohibited from competing in any elite women’s race between 400 meters and a mile.

After she won gold at the 2009 World Championships in Berlin — significantly beating her best time, set at the African Junior Championships the month before — questions about the 800-meter runner’s gender made headlines, and she has remained under intense scrutiny ever since. The International Association of Athletics Federations forced Semenya to take humiliating sex-verification tests to determine her eligibility to compete as a woman in the future. Through documents leaked to the press in 2009, Semenya learned, along with the rest of the world, that she has “differences in sex development,” or DSD, which for Semenya means her body naturally produces higher levels of testosterone than is typical for a woman, though what DSD means varies for individuals. Others have since used the results to talk freely about the most intimate aspects of Semenya’s life, and in 2019, the IAAF banned her from competing as a woman in her chosen categories. While she lost her legal battle against the restriction at a Swiss federal tribunal in 2020, the European Court of Human Rights found in July 2023 that Switzerland had not afforded her “sufficient institutional and procedural safeguards” to ensure that her complaints would be handled effectively. But the rules around forced testosterone suppression have not changed, and Semenya is still not allowed to enter elite races as a woman.

She talks about all this as if referring to something that happened to someone else, like a close relative. A solid coping mechanism, perhaps, for living through nearly 15 years of constant scrutiny and relentless prejudice on a world stage. She keeps her emotions close to her chest, but sometimes they surface in small controlled bursts — followed by an “I really don’t care.” The fact is, Semenya has dedicated her life to an industry that has treated her poorly. Yet resiliency, she points out, is what all athletes strive for: “You don’t care what other people say about you; you care about things that you can do.”

Semenya would rather her supporters hear directly from her, rather than from salacious op-eds and half-baked news pieces. Hence the memoir, which comes out October 31. “I owe them an explanation,” she says. But why now, 15 years after the hubbub started? “It was important to wait that long until I was ready to do it,” she explains. She reminds me that all athletes who compete at a high level have genetic advantages — not just runners but basketball players and swimmers, too — and hard work only enhances that potential. When men have supposed genetic advantages, they’re allowed to keep competing. “There are men with low testosterone; they can still run faster than me,” Semenya adds. But women are not afforded the same luxury. “People have their own way of explaining things, but one thing they need to understand is that, as humans, we are different, we are born different, we are given talents,” she says of her fellow athletes. “It’s a genetic thing, and there’s nothing anyone can do about it.”

Her story may be high profile, but Semenya isn’t alone in her struggle. Under various names, “sex testing,” “gender verification,” or “femininity testing” was introduced into sports in the mid-1960s to stop male athletes from “posing” as women. In 2020, a report by Human Rights Watch looking at a decade of experiences of people affected by the practice found it had disproportionately impacted women athletes from Africa and Asia. They are not only subjected to white, western ideas of femininity, which results in their being tested in the first place, but are less likely to have undergone nonconsensual “normalizing” procedures in childhood, such as the removal of their reproductive organs. In 2014, Indian sprinter Dutee Chand was dropped from competition after undergoing gender verification without her knowledge. In 2006, Santhi Soundarajan won silver in the 800-meter race at the Doha Asian Games but was stripped of her medal less than a week later after being found to have androgen insensitivity syndrome, a genetic condition that affects the development of genitals and reproductive organs.

Semenya appears more laid-back and amiable than the hard-ass she often describes herself as in the book, especially in her interactions with journalists who ask about her gender. Through fits of laughter, she notes she would even happily be photographed nude for the right price: “Let’s say Elle or Vogue say, ‘Here’s 1 million dollars for a cover, but we want you naked.’ There’s no second thought.” It’s a joke, but it’s not lighthearted — right beneath the wisecrack sits the underlying hope that if people could just see her sex organs, the debate would finally be settled. “It’s a frickin’ picture. You’re going to forget about it,” she says.

One memory Semenya will never forget is her first encounter with her now-wife, Violet Raseboya. They met in a women’s restroom in 2007, Semenya writes in her memoir, and Raseboya mistook her for a teenage boy. When I speak to Raseboya on Zoom a few weeks after I meet Semenya, she at first appears somewhat embarrassed to think back on this moment. “The minute someone tells you, ‘I’m not a boy, I’m a girl,’ you should respect that,” she says resolutely. Raseboya, now 37, was also an athlete. After years of friendship, the couple married in 2015. News platforms, in an attempt to discredit Semenya’s identification as a woman, scrutinized their wedding — everything from how they had courted each other to how they were dressed — and suggested that because Raseboya wore a full-length white lace dress and Semenya dressed in an embroidered velvet suit, they were conforming to stereotypical gender roles. Still, neither seems rattled by that issue. In LGBTQ+ communities, terms exist to describe their relationship. “We’re talking about the butch and the femme here,” Raseboya says. “So I don’t see a problem. We know where we stand.”

“From day one, I’ve understood I’m a different woman,” Semenya reiterates to me, having made this comment fairly seriously at the greasy spoon and again more casually at the pub. After finishing her water, she requests a ginger ale before turning to me and asking, “How old were you in 2009?” She’s wondering if I might have been too young to remember the initial media chaos. I note that I’m only a few years younger than she is, and she smiles and nods, clarifying what she already suspected: “You see, that’s what I’m saying.” It’s sobering to realize that when her public ordeal began, she was just 18, a legal adult but too young to experience the world openly scrutinizing her body. When she was growing up, her friends and family embraced her differences, and even though she knew she was unique, she never thought the difference between herself and most other women would so deeply impact the rest of her life. “I’ve always been myself, and I’ve always loved myself for who I am,” she says. “And people need to understand that where I come from, people accepted me.”

She does have one regret: taking medication from 2010 to 2015 to lower her testosterone levels. In the book, Semenya describes both the side effects, which included constant sickness and abdominal pain, and her doctor’s warning not to take the medication over the long term. In 2019, the World Medical Association, an independent international confederation of over 100 national medical organizations, advised against physicians’ prescribing athletes “unjustified medication, not based on medical need.” Initially, Semenya says, this “sacrificing” of herself came from a deep-rooted passion for running. “These are things I’ve done out of my will, out of desperation,” she adds solemnly. “But besides this, I’ve lived my life the best way I could.”

Semenya and Raseboya have been training future athletes through their Masai Athletics Club, a group the pair co-founded in Limpopo, and raising their two daughters, Oratile and Oarabile, who are 4 and 2 years old. Semenya’s experiences in the sporting world have given her an open-minded attitude toward embracing people as they are, especially when it comes to her children. “I am not going to force my kids to be who they’re not,” she says. “I’m going to accept anything that comes — who they are, what they want to do with their life — as long as they are happy.”

After writing an entire book about the constant public scrutiny she has endured, does it still exhaust Semenya to discuss her gender? “I can’t be exhausted to be myself,” she says, unfazed by the question. “People will always criticize you, they’ll always judge you. It’s part of life. But how you want to live your life is up to you.”

Related

https://www.thecut.com/2023/10/caster-semenya-race-to-be-myself-memoir-interview.html 1 Like |