Abstract Or Stylized African Art In Pictures - Culture (3) - Nairaland

Nairaland Forum / Nairaland / General / Culture / Abstract Or Stylized African Art In Pictures (33039 Views)

Must See - African Bravery In Pictures! / Igboukwu Art In Comparison To Ife Art - Taught By Exotic / African Art (2) (3) (4)

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (Reply) (Go Down)

| Re: Abstract Or Stylized African Art In Pictures by PhysicsQED(m): 4:28pm On Apr 14, 2012 |

Democratic Republic of Congo - Kuba Palm Wine Cup (Toledo Museum of Art) Democratic Republic of Congo Kuba peoples Wood Early 20th century "In the precolonial period, Kuba titleholders and other high-ranking officials drank palm wine from sculpted wooden cups in the form of human heads or full human bodies. The cups also served as display pieces. The faces are not intended as portraits of specific individuals, although they convey important information about identity. The hairline shown on this head is quintessentially Kuba. It is a style that was worn by men and women in the 19th and early 20th centuries by shaving a straight hairline with a curved or chiseled angle at the temples. The marks in front of each ear are scarification patterns, serving both as protective devices and as marks of Kuba social identity. The simplicity of the cup’s lines and the elegance of its form are accentuated by the richness of its deep red tone—the result of applications of tool, a red powder made from ground camwood and palm oil that Kuba people also apply to their own skin." |

| Re: Abstract Or Stylized African Art In Pictures by PhysicsQED(m): 4:30pm On Apr 14, 2012 |

Ivory Coast - Baule Gold Pendant (Toledo Museum of Art) Baule Peoples Ivory Coast Baule peoples early 20th century Gold cast and tooled While one might think of gold ornaments as a symbol of wealth in the material sense, Baule people ascribe a far more sacred value to this precious metal. For them, gold is “like a god” and is treated as an heirloom that evokes the presence of the ancestors. Baule families keep gold in ancestral treasuries called aja, which contain assorted prestige articles, including solid cast gold ornaments. This finely cast gold pendant in the form of a man’s face would have once belonged to such a treasury. The raised designs between the eyes and in front of the ears are cosmetic marks of Baule identity. It is a work of remarkable precision and delicacy and the entire piece conveys a love for gold that transcends its materiality. |

| Re: Abstract Or Stylized African Art In Pictures by PhysicsQED(m): 4:37pm On Apr 14, 2012 |

Democratic Republic of Congo - Hemba So'o Mask Monkey mask (So'o) Hemba peoples, Dem. Rep. of Congo Early-mid 20th century Wood H x W x D: 9 1/16 x 6 5/16 x 4 3/4 in. "This mask is called so'o, meaning "human chimpanzee." It has a human face and a chimpanzee's mouth. To the Hemba, so'o is a frightening, unnatural creature that represents death. The mask appears at the end of a long series of funeral rites to conclude the mourning period. Through a performance that moves from threatening to amusing, the mask helps people make the transition from grief back to their daily routine." |

| Re: Abstract Or Stylized African Art In Pictures by PhysicsQED(m): 4:54pm On Apr 14, 2012 |

| Re: Abstract Or Stylized African Art In Pictures by PhysicsQED(m): 5:01pm On Apr 14, 2012 |

Heddle Pulley. Côte d'Ivoire; Guro peoples, 19th century. Wood, pigment; H. 8 1/4 in. (21 cm) Provenance: Félix Fénéon, Paris, before 1929; Dr. Charles Stéphen-Chauvet, Paris; Morris Pinto, Paris, before 1985; Barbier-Mueller collection, since 1985 |

| Re: Abstract Or Stylized African Art In Pictures by PhysicsQED(m): 5:02pm On Apr 14, 2012 |

Mblo Twin Mask. Côte d'Ivoire; Baule peoples, 19th century. Wood, pigment; H. 11 3/8 in. (29 cm) Provenance: Roger Bédiat, Côte d'Ivoire, before 1955; [Henri Kamer, 1955]; Barbier-Mueller collection, since 1978 |

| Re: Abstract Or Stylized African Art In Pictures by PhysicsQED(m): 5:09pm On Apr 14, 2012 |

Ornament: Male Figure with Raised Arms. Mali; Inland Niger Delta, 13th–15th century. Copper alloy; H. 4 1/2 in. (11.4 cm) Provenance: [Merton Simpson, New York, before 1983]; Barbier-Mueller collection, since 1983 |

| Re: Abstract Or Stylized African Art In Pictures by PhysicsQED(m): 5:11pm On Apr 14, 2012 |

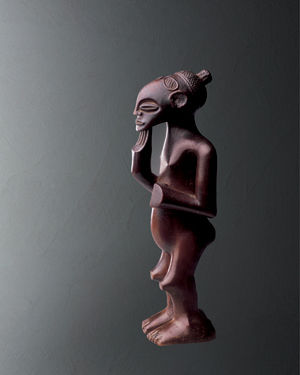

Female Figure. Northern Angola; Shinji peoples, 19th century? Wood; H. 7 3/4 in. (19.7 cm) |

| Re: Abstract Or Stylized African Art In Pictures by NegroNtns(m): 3:45am On Apr 17, 2012 |

PhysicsQED: Precisely, you hit it! In Yorubaland, the Efe is a deeper cult than the Gelede and though it is highly unlikely that a Gelede mask will pay tribute to a foreign culture but if it were to happen, amongst the many depictions they have, such tribute will definitely not come from Efe. The tribute is to Yoruba muslim and is a message admitting the oneness of the Yoruba traditional faith and the Islamic faith, represented in a way by the 7 amulets. While Islam forbids bowing or reverence to carved images and objects of cult worship, the Yoruba muslim, unlike the Hausa or Northern counterpart, is not intolerant of carved symbols and images. A Northern muslim will not acknowledge or appreciate such tribute from Efe. . . but a Yoruba would because they speak to a part of him that the Islamic indoctrination cannot totally block out - his/her cosmic consciousness! On the 7 amulets, there is no misspeak on their connection with Islam. |

| Re: Abstract Or Stylized African Art In Pictures by PhysicsQED(m): 12:40am On Apr 26, 2012 |

Thanks for the information, Negro Ntns. Definitely gives some insight into why they would sculpt an image of a Muslim and Islamic amulets specifically while being traditionalists themselves. |

| Re: Abstract Or Stylized African Art In Pictures by PhysicsQED(m): 12:46am On Apr 26, 2012 |

Baule linguists staff (?) / fly-whisk (?) Provenance: Walking Man Gallery Ex Kaba Collection Measurements: 15" tall |

| Re: Abstract Or Stylized African Art In Pictures by PhysicsQED(m): 12:55am On Apr 26, 2012 |

Lidded Container: Equestrian Figure, 16th–20th century Mali; Dogon Wood, metal staples; H. 33 3/4 in. (85.73 cm) The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979 (1979.206.173a-c) Metropolitan Museum of Art This elaborately carved, monumental container was used to hold food consumed during the investment rituals of Dogon religious and political leaders known as hogon. Hogon are the high priests of the cult of Lebe, the first Dogon ancestor to die, whose body was miraculously transformed into a snake after his death. Associated with regeneration and renewal, the cult is charged with maintaining the earth's fertility and ensuring the protection and well-being of Dogon society. This vessel's large size and visual elaboration indicates the hogon's importance within the life of a Dogon community. Its complex iconography can be interpreted using Dogon accounts of cosmology recorded in the early twentieth century. At the apex of the vessel, a heroic equestrian figure represents the hogon. The horse is a traditional indication of wealth, prestige, and social dominance, but in this context it also suggests the hogon's symbolic place within the Dogon cosmic order. It equates the hogon with Nommo, the mythic being that transformed itself into a horse to convey an ark carrying the eight primordial ancestors to earth. Two equine forms that support the container reinforce the hogon's connection to this moment in creation. Multiple female figures ring the vessel's base and originally surrounded the equestrian figure (only one remains at present), calling to mind the hogon's role in promoting female fertility within the community. |

| Re: Abstract Or Stylized African Art In Pictures by PhysicsQED(m): 12:56am On Apr 26, 2012 |

Metropolitan Museum of Art Container (Aduno Koro) with Figures, 16th–19th century Mali; Dogon Wood; L. 93 in. (236.22 cm) The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979 (1979.206.255) This monumental vessel, which is over seven feet long, was kept in the house of a lineage head in a Dogon community. It was used during an annual ritual known as goru to hold the meat of sheep and goats sacrificed at an altar dedicated to Amma the Creator and the family ancestors. Performed at the time of the winter solstice, the ceremony represents the culmination of rituals that celebrate the all-important millet harvest, whose abundance will support the family in the coming year. Such works have been described as aduno koro, an "ark of the world" meant to represent the mythic ark sent by Amma to reorganize and populate the world. The aduno koro displays a wealth of imagery relating to the Dogon account of genesis. Holding the eight original human ancestors and everything they needed for life on earth, the ark was guided by Nommo, the primordial being who created order within the universe. When the ark settled on the ground, Nommo transformed himself into a horse and transported the eight ancestors across the earth to water, where the ark floated like a boat. In this example, the horse's head is fitted with a bridle, representing Nommo's transformation into equine form, while the eight original ancestors are portrayed in two groups of four on the side of the vessel. The lizardlike creature separating the ancestors represents ayo geu, a black crocodile who killed Nommo after he completed his task of guiding the ark. |

| Re: Abstract Or Stylized African Art In Pictures by PhysicsQED(m): 12:59am On Apr 26, 2012 |

Bowl, Geometric Pattern, 19th–20th century; Fulani Fulani people; Mali, western Sudan Wood H. 5 3/4 in. (14.6 cm) The incised geometric decoration on the exterior of this dark brown hemispherical bowl consists of opposed triangles every 90 degrees separated by two bands of diagonal lines. |

| Re: Abstract Or Stylized African Art In Pictures by PhysicsQED(m): 1:04am On Apr 26, 2012 |

Ram Mask (Bata), 19th–20th century Kwele peoples; Republic of Congo or Gabon Wood, paint H. 20 3/4 in. (52.7 cm) Animal masks, known as ekuk, are used during ceremonies of the beete cult, a social association among the Kwele peoples. This bata or ram mask is distinguished by the curving horns that gently frame the face. The mask is relatively flat, with slight changes in plane clearly delineated by variations in color. The face, simplified to a heart-shaped form in the center of the mask, is highlighted in white. This delicate depiction of the face is a common feature in masks of the Kwele and other related ethnic groups in the surrounding equatorial forest region. The diverse repertoire of ekuk masks from beete ceremonies includes representations of the ram (bata) as seen here, the fierce gorilla (gon), and the swallow, among others. The Kwele are a Bantu-speaking people who live in the rain forests of western equatorial Africa (present-day Republic of Congo and Gabon). In principle, the regulation of village affairs was dependent upon the consensus of the heads of the resident lineages. In practice, consensus was rarely reached, and villages tended to fracture often. During the middle of the nineteenth century, a smallpox epidemic ravaged the area. The Kwele survived by obtaining a powerful "medicine" known as beete from neighboring peoples. Medicine here implies a complex ritual procedure that involves family relics, the visitation of nature spirits represented in masks, expiation and purification rites, and much more. The apparent success of beete in remedying this crisis, but also more importantly in combating the social fragmentation of the village and creating a sense of harmony and cooperation, led to its continued performance and elaboration by the Kwele. Most ekuk, which roughly translates as "things of the forest," feature prominent animal attributes while also maintaining an anthropomorphic face. The masks are considered representations of both important forest spirits and "children of beete." While the extensive preparations for beete ceremonies are in progress, multiple masks appear to prime the audience and create a spiritually "hot" atmosphere. The masks are used in morning and afternoon sessions to lead the villagers in dancing, enlivening the occasion with their beauty, movements, and suggestions of power. The beete ritual cycle includes the initiation of youths into the secret knowledge of the association; these candidates are introduced to the skulls of important past leaders as well as to masks of the beete. |

| Re: Abstract Or Stylized African Art In Pictures by PhysicsQED(m): 1:19am On Apr 26, 2012 |

Akuaba Figure, 19th–20th century Akan peoples; Ghana Wood, beads, string H. 10 2/3 in. Disk-headed akuaba figures remain one of the most recognizable forms in African art. Akuaba are used in a variety of contexts; primarily, however, they are consecrated by priests and carried by women who hope to conceive a child. The flat, disklike head is a strongly exaggerated convention of the Akan ideal of beauty: a high, oval forehead, slightly flattened in actual practice by gentle modeling of an infant's soft cranial bones. The flattened shape of the sculpture also serves a practical purpose, since women carry the figures against their backs wrapped in their skirt, evoking the manner that infants are carried. The rings on the figure's neck are a standard convention for rolls of fat, a sign of beauty, health, and prosperity in Akan culture. The delicate mouth of the figure is small and set low on the face. The small scars just discernible below the eyes of this figure refer to a local medical practice as protection against convulsions. Akuaba also function to protect against deformity or even ugliness in a child. During pregnancy, Akan women are not supposed to gaze upon anything (or anybody) physically unattractive, lest it influence the features of her own child. The traits that define the akuaba are meant as prayers or invocations for the physical beauty of an anticipated child. Most akuaba have abstracted horizontal arms and a cylindrical torso with simple indications of the breasts and navel; the torso ends in a base as opposed to human legs. The style of this sculpture is rare among other extant examples of akuaba due to its miniaturized naturalistic body, arms, and legs. Full-bodied figures such as this are believed to be a recent twentieth-century innovation within the akuaba sculptural tradition. The name akuaba comes from the Akan legend of a woman named Akua who was barren, but like all Akan women, she desired most of all to bear children. She consulted a priest who instructed her to commission the carving of a small wooden child and to carry the surrogate child on her back as if it were real. Akua cared for the figure as she would a living baby, even giving it gifts of beads and other trinkets. She was laughed at and teased by fellow villagers, who began to call the wooden figure Akuaba, or "Akua's child." Eventually though, Akua conceived a child and gave birth to a beautiful baby girl. Soon thereafter, even her detractors began adopting the same practice to overcome barrenness. All genuine akuaba are female images, primarily because Akua's first child was a girl but also because Akan society is matrilineal, so women prefer female children who will perpetuate the family line. Girls will also assist in all household chores, including the care of any smaller children in the family. After influencing pregnancy, akuaba are often returned to shrines as offerings to the spirits who responded to the appeals for a child. A collection of figures becomes an advertisement for the spirits' ability to help women conceive. Families also keep akuaba as memorials to a child or children. The figures become family heirlooms and are appreciated not for their spiritual associations, but rather because they are beautiful images that call to mind a loved one. |

| Re: Abstract Or Stylized African Art In Pictures by PhysicsQED(m): 1:27am On Apr 26, 2012 |

Figure (Grave Marker), 20th century Kenya; Giryama people Wood H. 67 1/4 in. (170.8 cm) The Giryama people of the Kenyan coast are known for their long-standing tradition of carved wooden mortuary posts. The grave posts, called kikangu, serve a number of functions within Giryama life. In the simplest sense, a kikangu stands as a grave marker. By honoring the power and presence of koma, or ancestor spirits, these grave posts also fulfill an important role as mediators between the world of the living and the ancestral realm. Giryama religious life revolves around this important relationship that strives to harness the constructive powers of koma and avoid any destructive influences. The abstract and geometric forms of kikangu serve as a diagrammatic representation of a spirit. The kikangu also serves as a record of the deceased's life and sometimes may even indicate the number of wives or the number of enemies killed in battle by the deceased. Grave posts such as this are schematic, and were not intended to be naturalistic. These simple-looking posts range from six to eight feet in height and eight to ten inches in width. The head portion of the post is usually flat and includes simplified representations of human features such as eyes, a nose, and occasionally a mouth. Buttons or coins are often used to represent the eyes, while the nose and mouth generally take on a rectangular form when featured. Often kikangu have both a frontal and a dorsal face. A thin rectangular neck connects the head to the long rectangular torso. The arms and lower limbs are not clearly delineated on this or most other kikangu. Most grave posts are carved of nzizi wood, an extremely hard wood that is also resistant to insect deterioration. The decorative aspects of Giryama mortuary posts feature a complex and harmonious interweaving of geometric shapes. The interlocking pattern of triangles on the torso of this example may serve as a mark of strength or power. The head features a circular pattern of triangles along the edge, which may symbolize radiating beams from a sunburst. The exact significance of these patterns is not known; they likely have multiple interpretations. Giryama burial rituals call for the internment of the deceased a day after death. The day after the burial marks the beginning of the mourning period. It is on this day that a kikangu is erected over the grave of the deceased. If the village moves, the kikangu is repositioned in the new locale. On a second migration, however, the kikangu is not removed. Another post, unlike the first and known as a kibao, is carved and erected instead. |

| Re: Abstract Or Stylized African Art In Pictures by PhysicsQED(m): 1:28am On Apr 26, 2012 |

Staff: Female Half Torso, 19th–20th century Angola; Ovimbundu Wood, brass tacks H. 17 7/8 in. (45.40 cm) This scepter was once part of a treasury of royal prestige items owned by an Ovimbundu chief in what is today north-central Angola. A finely carved and highly polished female head and torso comprise nearly one-half of its length. Elegant and refined, this idealized woman represents positive qualities the leader would wish to cultivate within himself. Careful attention has been paid to the accurate depiction of the elaborate coiffure, which is composed of two thick lobes swept backwards down the neck, and to the decorative markings on the skin. These bodily adornments, many of which would be received during an individual's transition into adulthood, were indications of social achievement and cultural integration. The figure's meditative expression, composed of downcast eyes and pursed mouth, combine with a bulging forehead to suggest intelligence and insight as well as deliberation and purpose. Decorative brass tacks embellish the base of the torso. Brass was an expensive, imported material that was drawn upon to enhance prestige items in this region. It served not only to beautify these sculptures and increase their value but also to indicate their owners' successful trading relationships with foreign powers. It is possible that the female figure on this scepter was inspired by royal art of the Luba kingdom to the north, in the southeastern region of present-day Democratic Republic of Congo. This important polity expanded its power and influence along trade routes that penetrated this region, forming alliances with smaller chiefdoms that eagerly adopted aspects of its prestigious political system and courtly art forms. Luba insignia of leadership enhanced with idealized female representations may have inspired Ovimbundu patrons to include these forms. The Ovimbundu chief who owned this scepter may have wished to associate himself with Luba ideals by emulating this characteristic element of Luba regalia. |

| Re: Abstract Or Stylized African Art In Pictures by PhysicsQED(m): 1:29am On Apr 26, 2012 |

Seated Chief (Mwanangara), before 1869 Angola; Chokwe Wood, cloth, fiber, beads H. 16 3/4 in. (42.54 cm) By the early nineteenth century, Chokwe chiefs in the savanna of present-day Democratic Republic of Congo and Angola had become active trading partners with merchants from Europe and the New World. Profiting from commerce in ivory, rubber, wax, and African slaves, they emerged as important regional rulers whose prestige and power was reflected in the art they commissioned for their courts at this time. This figure depicts a Chokwe chief, or mwanangara, and epitomizes the balance of power and refinement that is characteristic of Chokwe court art. His large, spreading hands, muscular shoulders, and aggressive posture epitomize the strength and vigor of a ruler. A bulging, domelike forehead and large eyes suggest mental acuity and keen eyesight. The sweeping curves and swelling volumes of the distinctive headdress, rendered here in wood, depict an actual Chokwe crown made of cloth-covered basketry. Horns of the tiny duiker antelope, which bear associations with hunting and the dangerous, mysterious practices of medicine and sorcery, are placed on the sides of the headdress. The chief holds a lamellophone, or "thumb piano," an instrument whose music often accompanies recitations of oral histories and the praise songs of important individuals. Instrument in hand, the chief is cast as a repository and guardian of historical and cultural knowledge. While depicting a nineteenth-century Chokwe chief, this sculpture also evokes the culture hero Chibinda Ilunga, a legendary hunter from the powerful Luba kingdom. Chibinda Ilunga is said to have introduced new principles of governance to the Chokwe peoples, and figures such as this one honor the productive union of these two cultures. |

| Re: Abstract Or Stylized African Art In Pictures by PhysicsQED(m): 1:30am On Apr 26, 2012 |

Maternity Figure, 19th–20th century Luluwa peoples; Democratic Republic of Congo Wood, metal ring H. 9 3/4 in. (24.8 cm) This intricately carved representation of a mother holding her child to her side is a Luluwa maternity figure. The figure belongs to bwanga bwa cibola, a social association or "cult" that addresses issues of human fertility and functions as part of the complex magico-religious world of the Luluwa peoples. Within this world, ritual healers known as mupaki or mpaka manga are endowed with mystical powers and play a vital role in the community by controlling and directing supernatural forces. Procreation is an essential goal in Luluwa society and consequently manga are often called upon to boost fertility and protect pregnant women, newborns, and small children. Manga utilize power objects, or bwanga, as containers and focal points of supernatural forces. The shape of the bwanga and the materials of which they are made vary greatly; many are natural, unworked objects such as gourds or animal horns, while others take the form of wooden anthropomorphic representations such as this example from the Museum's collection. The rendering of the mother figure conforms to accepted notions of beauty in Luluwa culture. Female beauty is an essential element in the ability to attract the ancestral spirits; it serves as an invitation to the ancestral spirits to inhabit the sculpture and thus exercise a positive influence on pregnancy, birth, and the health of the newborn. The figure's long neck and muscular limbs express positive aesthetic values. The concentric lines on the neck are either scarification patterns (nsalu) or necklaces, or possibly both. Luluwa women of status would often wear necklaces of blue and white beads to signify their rank. The large head and high forehead are indicators of beauty that also symbolize intelligence and willpower. The strong calves of the figure suggest a capacity for hard work, a quality much sought after by men when choosing a partner. The coiffure, jewelry, and extensive scarification patterns make apparent that this figure represents not only a beautiful woman, but one of high rank as well. The Luluwa associate body decoration with the unified notion of physical and moral beauty, in effect combining Western concepts of "beauty" and "good." At the same time, the nsalu are also a reference to human or cultural beauty, that is, beauty created by humans themselves. The coiffure depicted on this figure dates to the nineteenth century and consists of a vegetable-fiber wig, rows of cowrie shells woven into the hair at the back of the head, and a pointed shape at the top. Another significant characteristic of this figure is the protruding navel, which depicts the once highly coveted umbilical hernia. The navel symbolizes the close relationship between ancestors and progeny and also alludes to the succession of generations. The detailed depiction of a shell pendant between the shoulder blades of the figure is a direct reference to the cibola cult, as are the sculpted renderings of the loincloth and belt. The anthropomorphic conventions of this figure place it within a particular context of the artistic and sociopolitical history of the Luluwa peoples. Refined, intricately carved figures such as this are rare within the bwanga repertoire; most other examples are simpler, roughly hewn, and classified as "schematic." Scholars believe that the relatively "naturalistic" carving style was developed after the "schematic" style sometime during the mid- to late nineteenth century. It also appears that refined figures such as this belonged principally to a restricted class of women in positions of authority, which may also explain why such bwanga are so rare. The Luluwa were originally composed of a number of egalitarian groups. By the end of the nineteenth century, however, an unofficial but nonetheless very real class distinction had emerged in various regions of Luluwa territory. Naturalistic cibola figures, as much status symbols as ritual objects, are a likely result of this development. The production of naturalistic bwanga ended during the early twentieth century, when colonial powers subjugated the territory and curbed the power of the Luluwa elite. The most important factor contributing to the rarity of such pieces in Western collections remains the fact that most users did not preserve their bwanga. Manga and practitioners of cibola usually destroyed all their paraphernalia once their membership in the cult had ceased, and many other bwanga were placed at the grave or buried along with their owners. |

| Re: Abstract Or Stylized African Art In Pictures by PhysicsQED(m): 1:33am On Apr 26, 2012 |

Ladle, 20th century (before 1960) Zlan of Belewale Dan peoples; Liberia or Côte d'Ivoire Wood, pigment L. 23 in. (58.4 cm) Artists in Dan communities of the Guinea coast have mastered the art of carving impressive, large wooden spoons that are virtuoso works of sculpture. The spoons are known by many names, including wake mia or wunkirmian, which roughly translates as "spoon associated with feasts." The spoons range in size from a foot to two feet and have one or (rarely) two parallel bowls. The handle of the spoon is always decorated and often is related to the human form; this example features a carved representation of a woman's head. Her elaborate coiffure has two large crescents extending front to back and two small crescents arching over the ears. The oval face features slit eyes and a generous mouth that contains four metal tab teeth. The nape of the neck is decorated with scarification patterns that emphasize its beauty and strength. The long, slender, lobed neck leads to the bowl of the spoon, which itself is decorated with incised, linear patterns on the outside surface. Other wunkirmian may feature a pair of legs as the handle, as opposed to the carved representation of a head as seen here. Among the Dan, the owner of the spoon is called wa ke de, "at feasts acting woman." It is a title of great distinction that is given to the most hospitable woman of the village. With the honor, however, comes responsibility—the wa ke de must prepare the large feast that accompanies masquerade ceremonies. The excellent farming abilities, organizational talents, and culinary skills of the wa ke de are called upon to properly welcome and celebrate the masquerade spirits. When a woman has been selected as the main hostess of such a feast, she parades through town carrying the large spoon as an emblem of her status. On the day of the feast, she dances around the village dressed in men's clothes because "only men are taken seriously." She carries with her a wunkirmian and displays a bowl filled with small coins or rice. With help from her numerous assistants (usually female relatives or friends), she distributes grains and coins to the children of the community while dancing and singing her special shrill song. The deep belly of the spoon from which this bounty is dispensed becomes the symbolic body or womb of the female figure. The event creates a profound visual analogy that honors the hostess, and women in general, as a source of food and life. In addition to being emblems of honor, wunkirmian also have spiritual power. They are a Dan woman's chief liaison with the power of the spirit world and a symbol of that connection. Among the Dan, the wunkirmian have been assigned a role among women that is comparable to that which masks serve among the men. In many instances, wunkirmian are featured in the same ceremonies with masks, tossing rice in front of them as a blessing while they proceed through the village. This spoon is attributed to Zlan of Belewale, one of the most famous sculptors of the region. Zlan was actually a We sculptor who worked for many clients in several ethnic areas during the mid-twentieth century. In addition to being a great sculptor in his own right, Zlan was also a teacher who apprenticed many young carvers throughout his career. His work is featured in collections of the Peabody Museum at Harvard University, the New Orleans Museum of Art, and the French national collection in Paris. This is one of two works attributed to Zlan in the Metropolitan's permanent collection. |

| Re: Abstract Or Stylized African Art In Pictures by PhysicsQED(m): 1:34am On Apr 26, 2012 |

Twin Figurine, 19th–mid-20th century Côte d'Ivoire or Burkina Faso; Senufo or Tussian Brass H. 3 in. (7.6 cm), W. 1 7/8 in. (4.7 cm), D. 1/2 in. (1.3 cm) Twin or doubled imagery is a prominent feature of Senufo divination arts. Artists create twin figurines for the diviners and their clients who seek spiritual intercession to guide them in their work and secure their well-being. In this context, figurative pairs refer to coupled bush spirits, water spirits, biological twins, and otherworld partners.  Twin Figurine, 19th–mid-20th century Côte d'Ivoire or Burkina Faso; Senufo or Tussian Brass H. 2 in. (5.1 cm), W. 1 7/8 in. (4.7 cm), D. 1/4 in. (0.6 cm) Diviners in Senufo communities act as intermediaries between humans and potentially hostile nature spirits. The women's sandogo association trains many of the diviners in northern Côte d'Ivoire, but other resourceful men and women also learn how to divine. Clients seek consultations with divination experts when illness or disaster strikes, before pursuing a new project, or to prevent future calamities. Successful diviners depend on close interaction with nature spirits, or ndebele. They rely on artists to create works that will appeal to the ndebele spirits and induce them to relay messages between spirit and human realms. Early in their careers, diviners acquire relatively inexpensive arts, including figurines made of copper alloy. Doubled or twin imagery often refers to the bush spirits, water spirits, biological twins, and otherworld partners that assist diviners in their work. Open circles top the trapezoidal base on the stylized example shown here and suggest the two sets of eyes of paired or twinned figures. Once they establish their practices and develop a broad clientele, they invest in more costly wood sculpture. Diviners who are able to commission more expensive works usually retain the less refined ones as well. |

| Re: Abstract Or Stylized African Art In Pictures by PhysicsQED(m): 1:37am On Apr 26, 2012 |

Fragment from a Figure, Head, 16th–19th century Nigeria (?); Nnam Basalt H. 25 in. (63.5 cm) Over 300 monoliths carved from basalt in this style were created in the Cross River region of Nigeria between 200 to 1900 A.D. These lithic monuments, which vary in size ranging from around two to over six feet in height, are usually found in circular groupings facing inward. The depiction of human features in stone is unusual in sub-Saharan Africa; additionally, the scale, number, and arrangement of the Cross River monoliths distinguish them from other groupings of anthropomorphic sculpture. This particular example, with its elegant low-relief detailing around the eyes and the ornate cicatrization along the cheeks, led to its attribution to a class of objects created by members of the Nnam, one of eight clans that comprise the Bakor ethnic group of the Cross River region. Frequent motifs that appear on Nnam-style monoliths include a single spiral, double spiral, concentric circle, diamond, and triangle. This work is fragmentary and is the top half of what was originally a taller monolith. There is a clear differentiation between the sculpture's front and back, with the rear being devoid of inscription. The marks themselves refer to cicatrization patterns, which comment upon the wearer's level of initiation, ethnic, clan, and family identity. These markings may also relate to symbols that would have been painted on the body during festivals and ceremonies. All of the stones depict bearded figures, which suggest venerability and wisdom. Though these objects have played an important role in the ritual life of successive generations of members of local communities, their original purposes can only be conjectured. They may represent the spirit of deceased ancestors. It is also possible that they were created as memorials to important political and historical figures. Local people maintain that the stones were created by otherworldly powers and emerged out of the ground like trees. The difficulty that carving and transporting these stones would have represented to their makers—as compared to wood, which would have been more easily available and workable—is a further indication of their importance. |

| Re: Abstract Or Stylized African Art In Pictures by PhysicsQED(m): 1:38am On Apr 26, 2012 |

Janus-Faced Headdress, 19th–20th century Boki peoples; Nigeria Wood, cotton, metal, cane, pigment H. 14 5/8 in. (37.1 cm) This Boki headdress is the finest known example of its kind. Fewer than a dozen of these carved wood crests with cloth-wrapped attachments are known. It is unusual for masquerade ensembles to retain the mixed-media attachments with which they were seen in their original setting, and in this example they are not only beautifully executed but in an excellent state of preservation. Carved from a single piece of wood, the mask depicts two heads that share a single neck attached to a basketry cap. The neck, the areas below the chins, and the sides and tops of the heads have been covered with indigo-dyed, embroidered, strip-woven cotton cloth. Above each brow is a broad, curved "crown" made of basketry covered with similar embroidered cloth. Six cylindrical forms, also made of basketry wrapped with embroidered cloth, rise from the top of the head. The "crown" and the six cylindrical forms probably represent an elaborate hairstyle. The faces are broad and curved, with projecting open mouths and raised scarification marks on the temples, forehead, and cheeks. The faces are identical except for slight differences in the scarification marks and the patterns of embroidery on the coiffure. Both faces have metal inlaid eyes, and small brass pins inserted for the teeth. On one face, a row of small brass bells is attached along the jawline, while on the other is a row of teeth. There are a few known masquerade associations among the Boki, including nkang, egbege, and bekarum. This striking headdress probably belongs to the egbege association, a society reserved for women and responsible for a number of female affairs, most significantly the institution of fattening-houses for prospective brides. The origins of some motifs in this and other Boki works may be traced to numerous enigmatic stone monoliths known as akwanshi, located just south of the Boki peoples. The origin and significance of the monoliths is unknown; locals testify that the sculptures simply appeared out of the ground, but scholars believe they were carved sometime during the nineteenth century. Several of the monoliths feature raised scarification patterns on the cheeks, forehead, and temples similar to those found on this headdress. These patterns are said to have been historically common in the area. The attachment of brass bells and teeth to the jawline may also allude to antiquated fashions, as akwanshi feature long plaited beards that were ornamented with pendants of bone and brass. The elaborate linear patterns on the neck, chin, and coiffure are a reference to a sacred script known as nsibidi. The same patterns can be found throughout the region in other headdresses, embroidered and appliquéd on cloth, and even chalked on walls. There are still many gaps in the research regarding Boki material culture. Consequently, a concrete interpretation of the janiform composition of this Boki headdress remains unclear. Many scholars suggest, however, that the dual-headed representation may refer to the omnipotence and omnipresence of divine forces, as well as to male/female duality. |

| Re: Abstract Or Stylized African Art In Pictures by PhysicsQED(m): 1:41am On Apr 26, 2012 |

Face Mask (Kpeliye'e), 19th–mid-20th century Côte d'Ivoire, Mali, or Burkina Faso; Senufo Wood, pigment H. 15 15/16 in. (40.6 cm), W. 6 3/8 in. (16.2 cm), D. 3 1/8 in. (7.9 cm) The term Senufo refers to a group of more than thirty interrelated languages and the people who speak those languages in a region that spans the present-day national boundaries of Côte d'Ivoire, Mali, and Burkina Faso. Senufo arts and cultural practices display great regional variation. Three broad cultural divisions reflect general differences in dialect and sculptural style: southern Senufo in the region around the Ivoirian town of Katiola; northern Senufo in the vicinity of the Malian city of Sikasso; and central Senufo living in the vicinity of Korhogo, an important administrative center in Côte d'Ivoire. Bondoukou, Korhogo, and Boundiali, three cities across northern Côte d'Ivoire, have historically been centers where face masks have been produced and collected. Throughout the twentieth century, male performers wore raffia-fringed face masks, capes, and full-body outfits to entertain audiences at funerals, commemorative ceremonies, and other events in Senufo communities. Masqueraders' feminine dance movements pay homage to the importance of women. The face masks often emphasize feminine facial features and are embellished with geometric and figurative elements. The innovative sculptor who conceived of this delicately carved mask elongated the figure's nose to create an attenuated pointed beak and underscored linear design elements. |

| Re: Abstract Or Stylized African Art In Pictures by PhysicsQED(m): 1:42am On Apr 26, 2012 |

Memorial Head, 19th–20th century Côte d'Ivoire; Akan, Anyi subgroup Terracotta H. 10 3/8 in. (26.35 cm) This clay figure of a court musician was created to accompany a funerary portrait of an Akan ruler from what is presently southern Ghana or southeastern Côte d'Ivoire. When a ruler died, a memorial sculpture was created in his likeness and brought to the cemetery in which he was buried. It was left there with images created for previous generations of rulers, forming a display that was the focus of annual rites celebrating the memory of the royal ancestors. Sculptures of servants and courtiers such as this one were also left near the burial site, where they served to comfort and support the deceased in the afterlife. The unusual brimmed hat may indicate the courtly status of this royal servant. His striated neck suggests health and well-being, while the raised marks on his cheeks, temples, and forehead are skin embellishments that denote ethnic affiliation. His two arms raise a cylindrical flute to his lips. The work's somewhat abstracted form is quite expressive, as the backward tilt of the head and slitted eyes suggest a deep absorption in this creative act. |

| Re: Abstract Or Stylized African Art In Pictures by PhysicsQED(m): 1:43am On Apr 26, 2012 |

Seated Male Figure, 19th–20th century Ghana; Akan Wood, kaolin H. 19 in. (48.26 cm) This impressive image of a ruler was created by an Akan sculptor in what is today Ghana. The attention devoted to describing the chiefly regalia reflects the great emphasis placed on the courtly arts in this area. The Akan peoples were organized into several states of varying size and influence that were situated in a region rich in gold and ideally located for both overland and maritime trade. The Asante kingdom was the most important of these and at the height of its power controlled an area roughly corresponding to that of modern Ghana. An Akan ruler's appearance was thought to reflect the stability and well-being of his kingdom. Here, the figure's striated neck, softly bulging physique, and vigorous gesture suggest good health, while an abundance of accoutrements indicates the wealth and power of his court. These include a headband holding square ornaments, most likely of gilded wood, and a necklace, probably of cast gold. He is seated on a distinctive, five-legged stool whose arrangement symbolically evokes the organization of the kingdom: a central column, the king, is surrounded by four legs representing chiefs. In his hand he holds an afena, a curved sword with a spherical, gold-covered hilt and pommel carried by high-ranking officials of the court. The cloth wrapper that covers the ruler from the chest to his ankles likely represents kente, a brightly patterned cloth woven from imported silk. Finally, sandals cover the soles of the ruler's feet. According to Akan political practice, once a ruler was enthroned he could never touch the ground with his bare feet; to do so was said to pollute the earth and lead to famine and sickness within the kingdom. Wooden representations of male chiefs are relatively uncommon in Akan art, and it is not entirely certain for what context this work was created. The white clay, or kaolin, that coats the sculpture may associate it with spiritual practices during which the skin is whitened to indicate reverence and devotion. Similarly, carved figures of spiritual practitioners are frequently painted white to demonstrate their close links to the supernatural. |

| Re: Abstract Or Stylized African Art In Pictures by PhysicsQED(m): 1:51am On Apr 26, 2012 |

Container (Kuduo), 18th–19th century Ghana; Akan, Asante Brass, pigment H. 6 7/8 in. (17.46 cm) Ornate, cast brass vessels known as kuduo were the possessions of kings and courtiers in the Akan kingdoms. Gold dust and nuggets were kept in kuduo, as were other items of personal value and significance. As receptacles for their owners' kra, or life force, they were prominent features of ceremonies designed to honor and protect that individual. At the time of his death, a person's kuduo was filled with gold and other offerings and included in an assembly of items left at the burial site. The elaborate form and complex iconography of this kuduo reveal the broad range of aesthetic traditions from which the Akan peoples have drawn to create their courtly arts. Goods from Europe and North Africa, received in exchange for Akan gold, textiles, and slaves, included vessels that may have partly inspired the design of this and other kuduo. The repeating bands of geometric patterns incised into the surface, as well as the elegantly flaring foot, body, and handle, may reflect Islamic influences. A latch mechanism on the exterior reflects the value of the materials kept within and alludes to the vessel's symbolic function of keeping its owner's kra secure. |

| Re: Abstract Or Stylized African Art In Pictures by PhysicsQED(m): 1:52am On Apr 26, 2012 |

Pectoral Badge (Akrafokonmu), 18th–19th century Ghana; Akan, Asante Gold Diam. 5 1/2 in. (13.97 cm) Luxurious courtly arts wrought in gold are the prized emblems of leadership of the Akan peoples, and the Asante kingdom in particular, in what is today the modern nation of Ghana. By the mid-eighteenth century, the Asante kingdom had unified this culturally homogeneous region and asserted its control over trade in gold, textiles, and slaves. Asante's remarkable wealth and political vitality were symbolized by the extraordinarily rich art traditions propagated and sustained at the court by the king, or Asantahene. In Akan thought, gold is considered an earthly counterpart to the sun and the physical manifestation of life's vital force, or kra. Cast gold disks called akrafokonmu ( "soul washer's disk" ) are worn as protective emblems by important members of the court, including royal attendants known as akrafo, or "soul washers." Individuals selected for this title are beautiful young men and women born on the same day of the week as the king. Worthy of serving the king in light of their youth and vigor, they ritually purify and replenish the king's vital powers and, in doing so, help to stabilize and protect the nation. This akrafokonmu displays a central rosette surrounded by a circular border of repeating vegetal motifs. The inspiration for these intertwining leaves and tendrils may have come from North Africa, a region intimately linked to the Asante kingdom through the trans-Saharan gold trade. Even so, the composition as a whole reflects specifically Akan aesthetic concepts, in that the circular form of the disk and the concentric arrangement of the designs evoke the emanating rays of the sun that were the source of the kra of the king and his people. |

| Re: Abstract Or Stylized African Art In Pictures by PhysicsQED(m): 1:54am On Apr 26, 2012 |

Fante figures, Ghana wood, kaolin powder, beads (L) 16-1/4” (R) 14 1/2" ex Gordon Foster collection, NYC Fante Akua'ba figures are used in the same manner as those produced by the Asante people. They are generally carved with rectangular heads, unlike the circular heads of the Asante ones, and without arms. |

| Re: Abstract Or Stylized African Art In Pictures by PhysicsQED(m): 1:58am On Apr 26, 2012 |

Akan gold weight. |

| Re: Abstract Or Stylized African Art In Pictures by PhysicsQED(m): 1:59am On Apr 26, 2012 |

Akan peoples (Ghana), Kuduo (ritual vessel), 18th or 19th century, cast copper alloy. 21.9x16.8 cm. The Toledo Museum of Art, Toledo, Ohio. This container, called a kuduo among the Akan peoples of Ghana, was made from an alloy of copper using the lost-wax casting technique. Recent research suggests that they began being produced roughly 500 hundred years ago by Akan artisans. The prototypes for the kuduo were vessels produced in Egypt and Syria 500-700 years ago, and carried across the Sahara Desert by merchants who traded the Middle Eastern containers for gold. One of the richest gold producing areas of the world is found in what is today central and southern Ghana, the home of the Akan peoples. It is likely that these same merchants introduced the technology, lost-wax casting, used to produce kuduo and other important objects used as status markers in Akan society. It is interesting to note that there are no significant deposits of copper located in West Africa. Therefore, copper and its alloys came to be a valued trade commodity, first imported from the north and later from the coast of West Africa where, beginning in the 16th century, European merchants brought copper alloy artifacts to trade for Akan gold. Dating kuduo is difficult since the tradition, in effect, died out over one hundred years ago. A few kuduo are still in use, found in shrines and the treasuries of Akan chiefs, but no information about the origins of these objects is maintained. Most of the kuduo that are today maintained in museum and private collections, were found by accident while excavating new roads or digging the foundations for buildings. These objects do not carry any inscriptions identifying when or where they were made. Nor has a single kuduo been discovered in an archaeological context. In lieu of hard chronological data, one may hazard an educated guess that those kuduo that stylistically are most similar to the imported Middle Eastern vessels are the earliest examples of the tradition, and those that display Akan innovations, are later. We may tentatively date, based on style, the Toledo Museum of Art kuduo to the 18th or 19th century. This "casket" kuduo, with its hinged and hasped lid, is embellished with figurative imagery that one would not find on a metal vessel from the Middle East, a leopard attacking an antelope. Such imagery is tied to a verbal/visual mode of communication that is central to Akan culture. Visual images, both figurative and abstract, carry meaning associated with an enormous body of proverbs. There, for instance, are many proverbs associated with leopards and antelopes. In this case, the leopard/antelope is a metaphor for power--the power of a paramount chief over lesser chiefs, or a chief over his subjects. Kuduo were formerly made to serve as ritual containers used to hold the personal effects of wealthy individuals. They were often buried with their owner when he or she died. Examples like this one, ceased being produced at the end of the 19th century because there was no longer a local demand for such objects. However, by the third decade of the 20th century, kuduo began being produced again, but for the tourist trade. Though there are many fine examples, few "modern" kuduo match the quality of craftsmanship and elegance of form associated with the former tradition. |

What Are The Top 5 Black Cultural Foods/Cuisines To You? / Yoruba Men♥ / Popular Omens/superstitions In Idoma Land And Their Meanings

(Go Up)

| Sections: politics (1) business autos (1) jobs (1) career education (1) romance computers phones travel sports fashion health religion celebs tv-movies music-radio literature webmasters programming techmarket Links: (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10) Nairaland - Copyright © 2005 - 2024 Oluwaseun Osewa. All rights reserved. See How To Advertise. 150 |