| Defining The Afropolitan by Gbawe: 6:25pm On Mar 29, 2013 |

Any Afropolitans here? http://www.ariselive.com/articles/defining-the-afropolitan/95788/DEFINING THE AFROPOLITAN

DEFINING THE AFROPOLITAN

Image: (L-R) Yemi Alade-Lawal, Hannah Pool, Lulu Kitololo, Minna Salami and Tolu Ogunlesi. Photo credit: V&A Friday Late

Words: Minna Salami, founder of MsAfropolitan

Last month the V&A museum in London hosted What is an Afropolitan?, a panel discussion with myself, journalist and writer Tolu Ogunlesi, artist and designer Lulu Kitololo, Afro-Pop Live founder Yemi Alade-Lawal and ARISE’s new Features Editor, Hannah Pool.

We wanted to put our fingers on such topics as: what defines our generation of African diasporans? How do we incorporate the cultural voice of Africa with global and regional trends? And how are we changing socio-cultural perceptions of Africa?

I should first declare that we didn’t nail down a definition, and nor was that our aim. Rather, we participated in an exchange of perceptions, which was eagerly met by audience comments. It became clear that Afropolitanism means different things to different people – for some African is the more important element of the term, for others; cosmopolitanism. However, there was acquiescence that an Afropolitan is someone who vests part of his or her identity in the African continent.

Ultimately, the panel discussion showed a significant keenness to approach the topic and also that any conversation about Afropolitanism is inevitably connected to the African renaissance.

I’ll leave you with the words of Taiye Selasie, who coined the term. As the subculture develops, hers are sentiments that I hope it shall always harbour.

“What distinguishes [Afropolitans] is a willingness to complicate Africa – namely, to engage with, critique, and celebrate the parts of Africa that mean most to them. Perhaps what most typifies the Afropolitan consciousness is the refusal to oversimplify; the effort to understand what is ailing in Africa alongside the desire to honour what is wonderful, unique. Rather than essentialising the geographical entity, we seek to comprehend the cultural complexity; to honour the intellectual and spiritual legacy; and to sustain our parents’ cultures.” |

| Re: Defining The Afropolitan by Gbawe: 6:30pm On Mar 29, 2013 |

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/AfropolitanAfropolitan

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Afropolitan combines the words African and cosmopolitan to describe a contemporary generation of Africans. The term was popularized in 2005 by a widely-disseminated essay, "Bye-Bye, Babar (Or: What is an Afropolitan?)" by the author Taiye Selasi.[1] Originally published in March 2005 in the Africa Issue of the LIP Magazine,[2] the essay defines an Afropolitan identity, sensibility and experience. In 2006 the essay was republished by the Michael Stevenson Gallery in Cape Town[3] and in 2007 by The Nation in Nairobi,[4] whereupon it went viral. Several communities, artists, and publications now use the label, most notably The Afropolitan Network,[5] The Afropolitan Experience,[6] The Afropolitan Legacy Theatre,[7] The Afropolitan Collection,[8] and South Africa's The Afropolitan Magazine.[9] In June 2011 The Victoria and Albert Museum hosted "Friday Late: Afropolitans"[10] in London. In September 2011 the Houston Museum of African American Culture convened the symposium "Africans in America: The New Beat of Afropolitans,” featuring author Teju Cole, musician Derrick Ashong and artist Wangechi Mutu alongside Selasi.[11] |

| Re: Defining The Afropolitan by Gbawe: 6:34pm On Mar 29, 2013 |

http://edition.cnn.com/2012/02/17/world/africa/who-are-afropolitans/index.htmlYoung, urban and culturally savvy, meet the AfropolitansBy Mark Tutton, CNN February 17, 2012 -- Updated 1151 GMT (1951 HKT) Time Magazine has listed economist Dambisa Moyo as one of the "100 most Influential People in the World." Born in Zambia, Moyo went to university in the UK and the United States. Her books "Dead Aid" and "How the West was Lost" have been controversial and influential. HIDE CAPTION  Dambisa Moyo STORY HIGHLIGHTS The term "Afropolitan" is often used to refer to young Africans with a global outlookThe editor of Afropolitan magazine says: "I've kind of been raised by the world" Social media has been key to the movement, says blogger Minna Salami Movement is associated with a certain cool and a style influenced by Arise magazine (CNN) -- Young, urban and culturally savvy, meet the Afropolitans -- a new generation of Africans and people of African descent with a very global outlook.Something of a buzzword in the diaspora, the term "Afropolitan" first appeared in a 2005 magazine article by Nigerian/Ghanaian writer Taiye Selasi. Selasi wrote about multilingual Africans with different ethnic mixes living around the globe -- as she put it "not citizens but Africans of the world." Now the term has spread, used not just by New York hipsters and in trendy European capitals but in Africa's own multicultural megacities. But just who are these Afropolitans? Brendah Nyakudya is the editor of Afropolitan magazine, produced in South Africa. A Zimbabwean based in Johannesburg, who has lived in London, she has the kind of international background that typifies an Afropolitan. "I have African roots but I've kind of been raised by the world, and that's helped form my identity," she says. See also: Congo's designer dandies [size=14pt]An Afropolitan is someone who has roots in Africa, raised by the world, but still has an interest in the continent and is making an impact.[/size]Brendah Nyakudya, editor Afropolitan magazine Her magazine is aimed at successful urban 30-somethings -- intelligent, upwardly mobile and politically aware -- most of whom she says can be described as Afropolitans. "An Afropolitan is someone who has roots in Africa, raised by the world, but still has an interest in the continent and is making an impact, is feeding back into the continent and trying to better it," according to Nyakudya. She also believes the term can apply to non-Africans. "We like to think that it doesn't matter where you were born, if you find yourself on the continent and you love the continent, that makes you an Afropolitan," says Nyakudya. But for some people the term isn't so easy to define. Tolu Ogunlesi is a Nigerian journalist who is based in Lagos. He studied for his Masters degree in England and last year chaired a debate at London's V&A museum on what it means to be an Afropolitan. He says it's a problematic term and its meaning is hard to pin down. "It's one of those words that people invest with their own meanings, people interpret it as they want," he says. "Some people dismiss the concept entirely, saying there's nothing that people who are called Afropolitans share in common -- what they have in common is superficial." He feels the term is too often applied only to those living in the diaspora. "It's a problematic term because it's supposed to combine (the words) African and cosmopolitan," says Ogunlesi. "What it should mean is an African person in an urban environment, with the outlook and mindset that comes with urbanization -- people who live Lagos, Nairobi, and have this world-facing outlook. "But people who consider themselves Afropolitan are not here in the continent, they are out there in the global capitals." See also: Sounds of the Sahara Minna Salami, who blogs as Msafropolitan, is a true global citizen. Born in Finland to a Nigerian father and a Finnish mother she has lived in Nigeria, Sweden, Spain and New York, and now lives in London. She agrees that some people see Afropolitanism as existing only outside Africa, but says that, in reality, it applies just as much to people living in the continent. Some people have interpreted it as a diaspora movement but it absolutely isn't. Minna Salami - msafropolian "Some people have interpreted it as a diaspora movement but it absolutely isn't," she says. "When you go back to the original term 'African and cosmopolitanism,' Africa has very many cosmopolitan cities ... and in those cities you have art scenes and music and all kinds of creativity that's influenced by cosmopolitanism." For her it's a movement that is politically aware and has an obligation to correct decades of Africa being misrepresented as a "dark, failing continent." "Afropolitans are a group of people who are either of African origin or influenced by African culture, who are emerging internationally using African cultures in creative ways to change perceptions about Africa," Salami says. Salami adds that social media has been key to the movement, creating global citizens who are in tune with the same cultural trends and political issues. Ogunlesi agrees. He says that while ordinary Nigerians don't define themselves as Afropolitans, the prevalence of the internet and satellite television means young Nigerians do have a global outlook and are exposed to much of the same pop culture as youngsters all over the world. And social media also means that the coolest in contemporary African culture is quick to travel around the world. African and Africa-influenced pop culture is a key part of the movement. Afropolitanism implies a certain type of cool, with an aesthetic influenced by African style magazine Arise and a soundtrack provided by anyone from Nigerian musician Femi Kuti to South African "township tech" producer Spoeke Mathambo. But Nyakudya insists that to be a true Afropolitan takes more than a multi-cultural background and the right record collection -- it means having a commitment to making the continent a better place. She says: "From philanthropic work to trying to lobby for political reform there's a lot that needs to be done in Africa and if you're going to call yourself an Afropolitan you need to show what you're doing to deserve to be called an Afropolitan." |

| Re: Defining The Afropolitan by Gbawe: 6:35pm On Mar 29, 2013 |

David Adjaye is one of the world's most sought-after architects. Born in Tanzania to Ghanaian parents he is now based in London.  South African vocalist and producer Spoeke Mathambo has pioneered a kind of "township tech" that incorporates elements of electro, house and dubstep. His tunes can be heard on discerning dancefloors around the world.  Singer Mayra Andrade is a true globetrotter. Born in Cuba, raised in Cape Verde, she has also lived in Senegal, Angola and Germany, and now lives in Paris. Her jazzy bossa nova ballads are winning her fans all over the world. |

| Re: Defining The Afropolitan by Nobody: 6:37pm On Mar 29, 2013 |

Uncle Gbawe, ewo ni Afropolitan? could you break it down for me? abeg e don tey i go school. Ori mi ti fokasibe  |

| Re: Defining The Afropolitan by Gbawe: 6:40pm On Mar 29, 2013 |

Artist Chris Ofili was born in Manchetser, England to Nigerian parents. His work has drawn inspiration from a research trip to Zimbabwe. He is a former winner of Britain's prestigious Turner Prize for art, and his works include "No Woman, No Cry," pictured.  London-based fashion designer Hazel Aggrey-Orleans was born in Germany to a German mother and Nigerian father, and grew up in Lagos, Nigeria. She says her colorful designs reflect her multi-cultural background and global travels.  Andy Allo is a Cameroonian singer and guitarist who's now based in the United States. She has performed with Prince and produces what she describes as "alter-hip-soul.  Now 72 years old, South African musician Hugh Masekela proves you don't have to be young to be an Afropolitan. "Hugh Masekela is definitely Afropolitan," says Brendah Nyakudya, editor of Afropolitan magazine. "He has traveled the world but has come back and lives in Soweto with his people." |

| Re: Defining The Afropolitan by Gbawe: 6:44pm On Mar 29, 2013 |

http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2013/mar/22/taiye-selasi-afropolitan-memoirTaiye Selasi on discovering her pride in her African roots

The debut author of the eagerly anticipated novel, Ghana Must Go, writes about her shame at her family history and how she learned to be herself in Africa

Taiye Selasi

The Guardian, Friday 22 March 2013 16.43 GMT

Jump to comments (27)

'My mother was seven months pregnant when she learned her lover already had two wives' … Taiye Selasi in Lomé, Togo. Photograph: Taneisha Kamali Berg 2012

The crisis began – as crises are wont to do – at my best friend's wedding. Jamaica wasn't the obvious choice for what Jess likes to call "the whitest wedding on Earth". But there we sat smiling at the Rose Hall Ritz-Carlton, the hotel's all-brown staff smiling too. The salad had been served, the bread rolls broken and buttered, and now the reception began properly with polite conversation: how do you know the happy couple, where have you flown in from? I'd been placed between Clara, fair fellow alumna of Milton Academy and Yale University, and Percy, the third and presumably final husband of Jess's grandmum. With graceful concision, Clara told our tablemates where she came from: Brookline, prep school, Harvard Law School. Percy turned to me.

Tell us what you think: Star-rate and review this book

"And where are you from?" he asked in that accent I've only heard on Beacon Hill, in films about the Kennedys, and drinking with my agent. Boston Brahmin, baritone. A bit of extra weight on "you", as if the question mark belonged to me (the questionable thing), not "from". I gave the answer I always give, the answer I'd give if you asked me now, refined by years of daily practice, available in multiple languages. "I'm not sure where I'm from! I was born in London. My father's from Ghana but lives in Saudi Arabia. My mother's Nigerian but lives in Ghana. I grew up in Boston." Here I'll pause for reaction – soft chuckles of confusion, some statement along the lines of "You're a citizen of the world!" – then open the floor to any follow-up questions about any of the countries I've mentioned. Until last autumn at my best friend's wedding, I'd never really noticed the shame in this answer – which isn't to say that I'd never considered my angst about the question.

I had thought about it most cogently in 2005, having abandoned a DPhil in international relations to follow my dream, then some 20 years old, of writing for a living. Taking baby steps from footnotes to fiction, I wrote a short and personal essay on Africans who shared my trouble with the question "where are you from?". The piece – "Bye-Bye, Babar: Or, What is an Afropolitan?" – struck a chord with young Africans and people who love us, and by 2011 I was watching in wonder as my personal essay grew wings. It was a writer's dream: to have put into words some single truth of individual experience, to watch those words find a home in the world, that truth a thousand mirrors. "I am not an alien!" my self rejoiced. "I am not alone! There are others!"

There were. But they weren't at the whitest wedding on Earth. And here began the crisis. "How in the world did Jess find you?" asked Percy, chuckling. I bristled. My rattling off of disparate countries, well rehearsed, was meant to speak of international savoir faire, not render me a "find".

Clara kindly intervened. "Taiye went to Milton and Yale with me."

Still, Percy furrowed his bushy brows. "So you didn't grow up with your parents?"

"My mother raised my sister and me in Brookline," I offered.

"Without your father?"

"He's lived in Saudi Arabia for most of my life." I drained my wine and looked for more. Only now did I notice the room's demographics. "He's about to retire to Ghana," I added.

"Retire? Oh my! How old is he?"

"Seventy-five next year. My mum's much younger. She came third."

"Your father had three wives at once?"

A Jamaican waiter arrived with wine. But I couldn't steady my wine glass. I excused myself to go to the restroom and stumbled down the carpeted hallway, kicking off my platform heels and trying not to cry. A waitress, passing me, nodded with meaning and I nodded equally meaningfully back, in that gentle way in which brown people often acknowledge each other's presence. The instant's exchange reminded me of what I often overlook: my minority status. I'd just locked the stall when I started to sob, without quite knowing why.

❦

"Shame."

Thus spoke Ileane Ellsworth, my healer-cum-therapist-cum-psychic-cum-life-coach, attempting to release my solar plexus in her office on East 20th. It was an emergency session: I'd returned from Jamaica in emotional disrepair, unable to sleep or eat or stop crying, all because of one comment. "I wasn't ashamed! I was angry!" I raged. "He's a third bloody husband himself, for chrissake. If I were white, he'd never have thought my dad had three wives at once."

Ileane, beside me, pressed on my chest. "Why does this make you so angry?" she cooed.

"Because he's racist!" I cried. This may well not have been true. The truth came next. "And he's right."

Percy was right. My Saudi-based father, an incredible surgeon trained in Edinburgh, had two wives in Ghana when he proposed to my mother, his student in Lusaka. None the wiser, my mum said yes, and was seven months pregnant, in London, in love, when she learned that her lover was two women's husband and promptly went into labour. My twin sister and I arrived two months early, weighing three-and-a-half and four pounds respectively; our mum, herself an incredible paediatrician, nursed us back to health. Our father beat a swift retreat to King Faisal University in South Arabia to teach trauma surgery. Twelve years later we'd meet him again at Heathrow airport. Here – the year I transferred to Milton, befriending Jess my BFF – is where I first remember ever seeing the second of my parents. My mum had decided that it was time for us to know our progenitor and chose England as a halfway point between Al-Khobar and Brookline. Backstory: single, still living in London, she'd gone on a date with an American professor on sabbatical from MIT, visiting his cousin, the wife of the Senegalese ambassador. It was love at first sight. They married months later and returned to his faculty housing in Boston. A decade on, she'd left the husband but kept the job at Children's Hospital. So it was that I flew from Boston at 12 years old in LL Bean loafers, a British citizen with a suburban American accent, to meet my father.

Of course, all of this was missing from that standard issue answer in which I appeared a browner, younger Carmen Sandiego. "My father's from Ghana but he lives in Saudi Arabia" omitted the fact of his decade-long absence, while implying that I, too, was somehow "from Ghana", a tenuous claim at best. I was 15 years old when I first went to Ghana. I'd spent more time in Switzerland (where my godfather was a diplomat) and Spain (where my half-Scottish grandmum was mastering flamenco) than in Africa. I'd been to the continent only once before: to Nigeria, at seven and without my mum, whose painful adolescence in London and Lagos had left her with no love of home. "My mother's Nigerian but she lives in Ghana" omitted this fact: that she'd starved as a child, abandoned by her mother to fend for herself and her siblings on her grandfather's cocoa farm. It was my great-aunt who took me at seven years old to this family estate in Abeokuta, the famed hometown of Fela Kuti. I absolutely loved it. But my mum never taught me Yoruba – which I'd study, with comical results, at Yale – and I heard not a word of my father's Ewe until I turned 15. When I finally went to Accra that Christmas I discovered among other things: sugarloaf pineapple, hip-life music, and my father's other offspring. One was the child of his first wife Vivian; three of his (late) second wife Juliana; a fifth, of yet a different mum, had died under mysterious circumstances. As much as I adored the city of Accra, preferring it to Malaga and Lausanne by far, my first trip to Ghana was tainted by these fraught familial dynamics.

In the years to come I'd return for Christmases, not with my father but with friends of my mum. When she moved to Ghana in 2001 Accra became our base. My writing about Afropolitans took its texture from this sense of place, the tastes and smells and sounds that still make Ghana feel like home. And yet, hidden in my earnest exultation of Afropolitan-ness was an old and deep unease with being, very simply, African. In giving a name to a demographic, I'd assumed the role of advocate for more accurate portrayals of Africa – but wasn't sure I deserved it. Once, at a dinner for VS Naipaul, I was asked to toast Sir Vidia; I said, very genuinely, how much I admired how little he heeded his critics. Who was he to speak on behalf of the Caribbean, his detractors cried. Mine had a similar axe to grind: how African was I, really? Funny thing is, I'd resolved this particular identity crisis, at least for me. I was Afropolitan, dammit! I spoke for the Body AfroPolitic! It wasn't the identity issue – was I African enough to write about Africa? – that compromised my advocacy. No, the problem was my family.

There I was, heartily lauding Ghana in all of its peace-loving, hard-working glory, only to spiral out at one comment about my Ghanaian father. I was passionate about Africa, yes, but wasn't proud. I couldn't be. My tie to Africa – my African father – was standing in the way. Ileane was right. What I'd felt in Jamaica was shame about my family saga: the poverty, polygamy, one stereotype of African dysfunction after another. It had always seemed a matter of mere politesse to skip these sordid details when describing to a stranger who I was. But my grief at Percy's (spot-on) guess suggested something else at work: a need to obscure both where and who I came from. Intellectually, I perceived myself as a product and champion of modern west Africa. Emotionally, I perceived myself as a west African polygamist's daughter. What I needed was some other way to know myself as African, apart from as heir to my parents' hurts.

For this, I had to go home.

❦

"Home."

That very heavy word, with all the flaws of all ideals, a standard nowhere ever meets, a gold and leaden star. For 15 years I'd gone to Ghana desperately seeking home writ large, ignoring my role in the relationship, the "I" in "I had to go home". For half my life I'd travelled home and left myself, my truth, behind: arriving in Ghana and assuming the role of (illegitimate) Prodigal Daughter. I was disappointed, naturally, in the ways that home-seeking prodigals are, dismayed to find my otherness in tact among my own. But I had never been myself in Ghana. The self I'd become in 30 years: the author, photographer, screenwriter, traveller, designer, thinker. I'd spent months at a time in Oxford, Paris, New York, New Delhi, and always felt at home: for I experienced those cities, experienced myself, as a creator, not a creation. Returning home after Jess's wedding – to Rome, my latest choice of city – I wondered at this: I'd never created an experience in Africa. My father had, my mother had; they'd dreamed and learned and loved, and left. I'd walked in their shadows, but not in my shoes. It was time for a trip.

❦

The summer I finished my first novel Ghana Must Go, I drove across west Africa: from Accra to Lomé to Cotonou to the deliciously named Ouagadougou. This time I took myself along, my writer-traveller-photographer-self, with a project: photographing twentysomethings in 54 African cities. The stated aim was a photography book, a collective portrait of the young adults so conspicuously absent from western media's portrayals of urban Africa. The politically minded observer in me had grown weary of the imagery: the wizened elders, the wide-eyed children hugging volunteers. So I armed myself at B&H Photo and asked two friends to come along: Bliss Holloway the cinematographer and Taneisha Berg the documentarian. Our cheery if cash-strapped crew set off to capture the birth of my photo project – but six weeks in it was suddenly clear that there was a film to be made. We've now resolved to fundraise for a full-length documentary: a lively look at the days and dreams of African twentysomethings.

Of course, my deepest aim was personal: not to "find myself" in Africa but to be myself on African soil. This I did. And how. In Ouaga I danced until 5am at Allapalooza, a western-themed club, watched movies at a feminist film festival, wandered a sculpture park in the desert. Adama, our charming host, was an Afropolitan of the highest order: a Muslim musician with a Viennese wife, studying German at the Goethe Institute, uninterested in living anywhere else apart from Burkina Faso. Togo was a seaside treat: like Malibu with motorini, miles and miles of white-sand beach and perfect rows of palm trees. Thursday at midnight, we stood on that beach with hundreds of super-cool Togolese hipsters, assembled for the weekly late-night car tricks show and drag race. Cotonou was magic, too: I learned to sail in a hidden lagoon, swilled Eku (Afro-Bavarian beer) at Saloon, a riverfront bar. But the hometown – Accra – was the real revelation, what with its International Salsa Congress, midnight swimming at La Villa Hotel, guitarist Serwaa Okudzeto. The city had changed, but not so much; I felt it differently, intimately. I could see myself in these African cities: a designer in the vibrant clothes, a screenwriter in the desert scenes, a poet in the rhythms. I began to say that I wanted an "I ❤ Heart of Darkness" T-shirt, and only half in jest. The journey had cured my Percy Problem at last. This wasn't my parents' Africa, the past, that static site of hurt and home. It was mine: dynamic now. This wasn't some "real" west Africa either. It was my west Africa, my version of home, not just a place, but a way to be in – a way to know – the world.

❦

Leaving Accra to fly back to Rome, I presented my passport at customs. The Ghanaian agent, reading my name, didn't bother with "where are you from?". "Selasi! So you're an Ewe!" He beamed.

"My father's …" I started, then stopped. I smiled. "Yes. I am."

"Safe journey," he said. "Come home soon."

"I will." |

| Re: Defining The Afropolitan by Nobody: 6:44pm On Mar 29, 2013 |

Oh now i understand! these people are more of celebrities than Afropolitans. or are both the same? |

| Re: Defining The Afropolitan by Gbawe: 6:50pm On Mar 29, 2013 |

http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2013/mar/22/taiye-selasi-interview-ghana-mustTaiye Selasi: 'I'm very willing to follow my imagination'

The 'Afropolitan' novelist on escaping a yoga retreat, rejecting routine – and the upside of heartbreak

Share 14

Interview by Tim Lewis

The Observer, Friday 22 March 2013 12.00 GMT

Jump to comments (2)

Taiye Selasi: 'I’ve often wondered if writing is just a socially acceptable form of madness.' Photograph: Nancy Crampton

Taiye Selasi is the embodiment of "Afropolitan", a word she coined. Born in London, to a Nigerian mother and Ghanaian father, the 33-year-old writer and photographer grew up in the States and now lives in Rome. Her debut novel, a sprawling, globe-trotting family saga called Ghana Must Go, has received enthused endorsements from Toni Morrison and Salman Rushdie, and she is one of the Waterstones 11 for 2013.

Ghana Must Go

by Taiye Selasi

Buy it from the Guardian bookshop

Is it true that the idea for Ghana Must Go came at a yoga retreat in Sweden?

Absolutely. It was 5am and I was in the shower and everyone in the novel was there in an instant. But the retreat didn't allow electronics, so I had this epiphany, this revelation – here's the novel, these are the people, this is their story – where's my laptop? Nothing doing, so my friend and I sort of escaped, took the train to Copenhagen, and that's where I began the novel.

We like to think that moments of inspiration will come on yoga retreats – is that your experience?

No, the thing that comes most frequently to me on yoga retreats is excruciating pain in my hips. Toni Morrison said that she wrote her first novel because it was the book she wanted to read; I think this novel came to me like that. It was entirely realised, like remembering a book I'd read, except I thought: No, I haven't read that. So I had to get to work.

That must often happen with debut novels – you pour your whole life into them…

To be honest, all my work comes that way. The big ideas always come in flashes. I don't really craft stories that much. I genuinely don't know where these people come from and I've often wondered if writing is just a socially acceptable form of madness.

Routine is important for a lot of writers, but you wrote Ghana Must Go in Nigeria, Ghana, India and Rome…

I found there were three things I needed and still need to do the work: silence, light and a sense of space. But I'm very willing to follow my imagination where it wants to go, rather than dragging it around behind me or unleashing it and teaching it to sit and roll over. I still read bits of Ghana Must Go – before bed, I sometimes open to a random page and gaze at it lovingly – and I think to myself: I don't know even know this. Genuinely, if I, Taiye, knew everything Ghana Must Go knows collectively, I would not suffer heartbreak, I would not suffer any of the petty human woes that I continue to suffer on a regular basis.

So you completed 100 pages of the novel, got a book deal and then there was the little block…

What do we call it? The little block! It was six months long, those were the dark days.

You thought you might never write again?

I did, but every blocked writer does. That's what makes writer's block so painful. You think the well has run dry, maybe somewhere in the heavens the tap has been turned off. That's beyond frightening. That has nothing to do with deadlines, contracts signed or advance money spent, that has to do with the fear of losing your joy, your love. I was heartbroken. But then of course I was really heartbroken. I was heartbroken by the man I was foolishly dating at the time. Then I was able to finish the book!

What do you do now when you're stuck?

I live in Rome and five minutes from my flat is a church where you can walk in and see this beautiful Caravaggio. Just the way this man uses dark paint: dark to create dark to create dark, the layering of the darkness in his work. I just race home: I want to create! |

| Re: Defining The Afropolitan by Gbawe: 6:59pm On Mar 29, 2013 |

berem: Oh now i understand! these people are more of celebrities than Afropolitans. or are both the same? They are the celebrity faces of what an Afropolitian is. An Afropolitan, simplistically, is anyone who is an academically and professionally successful 'citizen of the world' with an African background they are proud of and identify with passionately. In fact, one thing many Afropolitans will have in common is the passion for Africa that draws them into collaborative endeavours/association with the continent regardless of where they live. Afropolitan is simply a witty and thematic spin of cosmopolitan. |

| Re: Defining The Afropolitan by Gbawe: 7:07pm On Mar 29, 2013 |

http://www.msafropolitan.com/afropolitanAfropolitan Quotes

An afropolitan is anyone who is African and identifies with the African continent, either black or white. A person who shares the vision of a better Africa, whose sympathies and loyalties are with Africa. Anyone who happens to have a cosmopolitan outlook and is ambitious on a personal level, economically and intellectually is an afropolitan.

Tiisetso Makube, editor of The Afropolitan

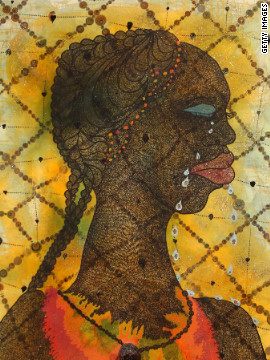

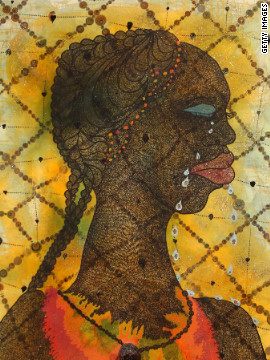

At the same time they understand, it would seem, that their choices have weight. Postcolonial African art, wherever it is produced, is all but inseparable from politics. In Africa art has always played a social role, assumed moral status, a status that even physical distance …can’t erase.

And so Afropolitanism, young and cool, comes with responsibilities.

Holland Cotter, Pulitzer Prize winner, critic

As I see it, the vocabulary of racial freedom is not enough to deal with these questions. What needs to be done is to discover a language within which these fractured linkages can be understood and redeemed.

I suggest that Afropolitanism is that language and that concept.

Professor Achille Mbembe

Afropolitanism is ” a mindset rather than a project. A mindset of being ‘comfortably African’ in the way described above, driving a myriad of projects, collaborations and engagements. A strong pillar of Afropolitanism is our desire to specialise in knowledge on and about Africa. This is achieved through a variety of initiatives and engagements, from research collaborations to co-supervision of postgrads; from joint curriculum design to staff and student exchanges; from external examining to joint participation with continental partners in global networks.

Professor Thandabantu Nhlapo, deputy vice-chancellor, UCT

An Afropolitan, simply put, is an African who vests their identity in the African continent as well as in hybrid spaces of diaspora, migration, locality, globalism, multilingualism and so on. However, Afropolitanism is an evolving movement and a tricky idea to define conceptually. This probably has to do with scales, how much one sees Africa and how much one sees cosmopolitan in the term.

Minna Salami, editor of MsAfropolitan.com |