ChinenyeN's Posts

Nairaland Forum / ChinenyeN's Profile / ChinenyeN's Posts

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10) (11) (12) (13) (of 223 pages)

Igboid: This is foolish. I honestly cannot believe what I just read. You’ve been on NL long enough and interacted with me long enough to know better, but you’re just here carrying along with the stupidity spewing from Eastlink’s mouth about me. I’m going back to the Culture section. I don’t even know why I tried to show you a modicum of modesty and goodwill by responding to your request for my thoughts on the original post. I won’t be responding to anything else on this thread. 3 Likes |

This is the reason why I left the politics section, because you people are hopeless. The British created hard ethnic lines that did not exist before and you people have been running crazy with it ever since. Igboid: And saying a lot of wrong things in the process. So what does that tell me? They are willing to lie, just to discredit Ijaw. It’s Ijawphobia. The same way Alagoa was willing to fabricate things just to diminish the idea of Igbo in Bonny’s history (Igbophobia). None of you want to be honest about culture, history and language. You all just want to find ways to weaponize it as politics for yourselves. As if it will change anything in your present day. Igboid: OP did not rationally deduce anything. Umueze is recognized as having migrated in the company of Ijaw people. If the OP really wanted to rationally deduce something, they would have first been honest about Umueze’s migration and then deduce that perhaps Central Delta Ijaw migrated northwards and came into contact with some Igbo-speaking people who claim a “Benin” history. These two populations then migrated together and ended up in Ndoki. After a brief sojourn, some proceeded to migrate to Bonny. That would have been rational, because Umueze migration acknowledges Ijaw. Igboid: Again, Umueze’s oral tradition acknowledges Ijaw in this migration. This is not a fabrication. Alagoa definitely took that opportunity to exaggerate and fabricate that all of Ndoki are from Central Delta. But just because Alagoa lied does not make the Umueze tradition any less true. They were in the company of Ijaw when they arrived at Obunku. There is no other way to spin this, unless you want to start erasing some Umueze oral tradition the same way Alagoa tried to erase some Bonny oral tradition. |

cheruv: Two oral traditions exist to explain this. 1. Some conflict between Ndoki communities and Bonny led to the phrase “anyi na-ado ke?” (What are we fighting for?). Some Ndoki people (who are typically anti-Ijaw) have been pushing this tradition as of late. 2. During the reverse migration, Ijaw from Bonny/Opobo came looking for communities that they identified with as “minabo” (sibling). The phrase developed “a mina dokiari” (I am looking for my sibling). The name “Ndoki” is supposedly derived from here. Between these two, I’m more inclined to believe the second one. There is a lot of cultural, historical and linguistic basis for this. Between Bonny’s long history with Umuagbayi, Azuogu, etc. (Bonny’s founding ancestor being literal kin with Umuagbayi’s founding ancestors), Umueze’s migration into the area alongside Ijaw, along with the fact that some of Umueze’s early ancestors had Ijaw names, the “a mina dokiari” tradition makes sense to me since all of this compounds into a strong sense of kinship between Bonny and Ndoki communities (which is well-acknowledged). 2 Likes 1 Share |

Igboid: I don’t know who the OP (original poster) is, so I won’t offer up any opinions on them per se. But it’s possible you mean OP as in “original post” (the post itself). In that case, I can say a few things about it. To begin with, I can’t say I disagree with the writer’s premise. Anyone who casually examines the ethno-linguistic history and traditions of origin in the area will find it near impossible to claim beyond a doubt that Ndoki and Bonny don’t have ancestral, non-slave, Igbo-speaking origins. So that part is agreeable. It’s just that a lot of what the writer says to support the premise in this write up is questionable. Truthfully, I think the original post is rather “Ijaw-phobic”, if I can use that term. The writing is so heavily anti-Ijaw that it ends up discrediting itself at times. If you dig even a little, the write up shows a lot of inconsistencies and even some outright wrong things. Ndoki traditions of origin is traced to Oguta, it has variations but all accounts are consistent about one point, Oguta, some talk of Benin before reaching Oguta but this can be understood as a result of the relationship between Oguta, Aboh and other Ndoshimili towns with Benin which the Ndoki brought such tales with them as they were leaving Oguta, If this is limited to the Umueze clan, then I can understand where the writer may be coming from. One of the oral traditions in Umueze claims a long-winding history of migration from Benin or Central Delta, entering “Igboland” from the south and then cutting northeast towards Oguta, etc. However, Umueze has never claimed Oguta as its homeland. Even before this “Ijaw vs Igbo” saga started, the Umueze never mentioned Oguta as ancestral homeland. It’s always been either Benin or Central Delta Ijaw. The writer could possibly be making a supposition here that Ndoki (Umueze) are part of that set of Ndoni-Abo-Oguta communities near the Central Delta. It’s not a bad supposition. However it is not a claim that has ever been made by Ndoki people, not even in early intelligence reports. Now, if the writer is not limiting this to Umueze and is instead referring to all of Ndoki, then this would simply be wrong. Ndoki is not from Oguta. Their traditions do not trace them to Oguta. the name.originated as a nickname for the Ndoki group and it was given them by none other than the Ogoni The writer got this wrong and ended up confusion themselves in the process. It is actually the ethnonym “Ogoni” (and not Ibani) that refers to a “guest” or a “stranger”, derived from the Ijaw word “igoni”. This tradition is plausible because the Ndoki to get from Umuagbai to Bonny has to pass through Ogoni land, the first point they settled on the coast before finally crossing onto the island was just adjacent to Ogoni, This is not, actually. To begin with, Ogoni traditions actually acknowledge that they are not the aboriginal settlers in the area. Much of what is “Ogoniland” was acquired bloodily through conquest and the absorption of already existing communities. There are two main Ogoni traditions of origin. The tradition that has the most support claims that they migrated east to west, crossing the Imo (from present day Akwa Ibom) to settle in the area. The second tradition claims that their ancestors arrived on trading ships that would visit Bonny. They lived in Bonny for a while and later felt the need to move further inland to settle (Bonny traditions I believe suggest that this is how they got their name). Regardless of which tradition is the “correct” one, the dating for both of these (as far as I see it) can at best be justified at the 17th/18th century or so. This is centuries after Bonny was founded. There would have been no Ogoni to interact with at the time and when you survey the oral traditions of the entire Niger Delta, you’ll notice the absence of Ogoni in the communities’ early traditions. Early Asa traditions and early Ngwa traditions make no mention of Ogoni. Early Bonny traditions make no mention of crossing through Ogoni communities to settle. Okrika and Kalabari traditions show no early memory of Ogoni, and (to the best of my knowledge) even the Ogoni themselves have no traditions that mention how the other communities arrived and settled, meaning they could not have been in the area during those formative periods. For a long time the Ogoni and neighboring people referred to the island as Bani after the strangers and the people as Ebane, this name is attested for by W.Baike in 1854 in "Narrative of an Exploring Voyage" p.380 writes, "The Bonny people claim an Igbo descent, their territory which is not very extensive is by them pronounced Ebane, by the Igbos it is pronounced Obane, and by the Kalabari : Ibani" If we take a survey of ethnonyms within the Niger Delta region, we will notice some ethnonyms that are used exclusively by Ijaw. Where the natives will call themselves “Obolo” and others will call them “Andoni”, only the Ijaw will call them Idoni. Where the natives will call themselves originally as “Khana”, others will call them “Ogoni”, but only the Ijaw will call them “Igoni”. Where they natives called themselves “Okoloma”, and others call them Ubani or Obani, but only the Ijaw will use “Ibani”. There is a clear pattern of derivation here and a clear pattern of consistency in Ijaw usages. It suggests that the name “Ibani” (like "Ogoni" and "Andoni" ) is likely derived from Ijaw. While I do agree with the writer in that I am suspicious of Alagoa likely having fabricated some stories and migrations during the Ijaw re-authorization period, there nothing to suggest that this is one such fabrication. The term “Ibani” likely comes from Ijaw and was derived into Ubani, Obani, etc. by others. Ndoki towns after they settled at Azumini were all Igbos, the supreme ancestor was called Eze, his children were Ihu(umuihueze group) iloko (Obohia group) and Kwokwo (kwokwoeze group) others such as Ikwueke, umuokobo, Azuogu, Agbai, Ayama are all Igbo names. This is incorrect on a number of points. One, “Ndoki” is a collection of clans that do not claim a common ancestor. Eze is only the progenitor of Umueze clan. The Umueze clan are noted by other Ndoki clans as recent arrivals. They arrived in the late 18th century in the company of Ijaw people. Azumini is also one of the youngest settlements in the area, established by Kwokwo Eze (a son of Eze). Umueze first settled at Obunku Okwanku. That said, the writer is correct on one count. All of the founding/early communities in Ndoki seem to have been Igbo-speaking. The aborigines which the Ubani met when they touched Bonny were an Ibibioid people known as Inyong Okpon, who are also the aborigines of Tombia. They had a chief priest called Awanta, for centuries the Ubani lived side by side with these aborigines until in the 18th century a late Eastward expansion of Ijaw groups (Awome who are the precursors of the Kalabari) brought Awome settlements directly into the region, they assimilated much of the Inyong peoples just as they did at Elem and established canoe war houses, that was how Ijaw culture gradually diffused into the daily life of Bonny More or less correct. Apparently, it is corroborated that there were two other communities in the vicinity during Bobby’s early days, Abalama and Inyong Okpon (what later came to known as Finima). However, contact between these communities was not during initial settlement. According to one tradition by Finima, their boundaries grew into each other and that is how they became aware of each other. Fixing a chronology for their interactions has been a little difficult, because some claim they were there since the 12th century, but some specifics in oral traditions hint as a later date of a perhaps the 15th century or slightly later. I suspect that they all more or less arrived at the same time and that they likely became aware of each other a bit late in their early histories. However, that is just a suspicion. Until the oral traditions can be thoroughly untangled and a chronology can be reasonably established, I will tend to just go with the current orthodox traditions that Inyong Okpon was likely there first, followed by Abalama and then Bonny. So, if we want to follow hard ethno-linguistic lines, Ibibiod (Inyong Okpon), Ijaw (Abalama), and Igbo (Bonny, though contested) were all in the area during that formative period. Ndoki language however still remaimed the lingua franca and dominant culture in Bonny as attested by many British colonists in the region, the first Igbo bible written by the missionaries was done using the Ndoki dialect of Bonny. No. Once the social-political culture shifted in the 18th century, so did the lingua franca. The lingua franca of the controlling Conoe Houses was Ijaw. The language used by Bonny leadership, used for official rites, ceremonies, festivals, music, and all sorts of culture, was Ijaw. Igbo-speaking was for commoners and trade as things were shifting into the Palm Oil trade era (dominated by Ngwa, Asa and Ndoki). Many Ijaw dissenters love to attribute the igbo presence in Bonny to slaves should note that majority of the slaves in Bonny were Isuama in origin but isuama is not spoken in Bonny neither is Isuama culture or deities to be found in Bonny, More or less correct. Except Ikuba is from Andoni, not Ndoki, if I recall correctly. And Tolofari is Ijaw. And lastly is the Nwotam masquerade, which is danced by the Ndoki, Ubani and Opobo alike, originated from mkpaejekiri in Ohambele Ndoki, people who watch Nwotam in Opobo and Bonny would note that it has maintained it's igbo language, the dance steps and the different guilds(uke) are igbo and the oja music and dance style and rythm is distinctively Igbo. Mostly correct on this account. The version of Nwotam practices by Bonny and Andoni comes from the one from Mkpuajekere. Other variants of the masquerade exist in Ngwa and Asa (as Nwutam), but not the guild form developed by Mkpuajekere and consequently spread to Bonny and Andoni. The man who led the Ubani from Ndoki now known as Agbaria and his friend Okpara Ndoli This is more or less in line with most of the traditions of origin. The first settlement of the Ndoki on the Azumini creeks was on a place called Okoloma, which name came from the aborigines. This curlew tradition is independently referenced and corroborated by Ngwa, Ndoki and Bonny-Ijaw communities. This is not a fabrication but instead an actual oral tradition shared by multiple communities in the region. As stated earlier, the first settlement of Ndoki (Umueze) was Obunku Okwanku. The Okoloma in Ndoki are a recent settlement part of a reverse migration that occurred in the 19th century as a result of the civil war (Bonny vs Opobo) and ongoing conflict with other Niger Delta trading states . There fore any scholar who is honest would learn that Bonny has been a product of mix of peoples, Aborigines, Ijaw and Ndoki with the Ndoki elements being majority, It would take a lot to respond to this effectively, so perhaps I’ll leave much of it for another day and just say that yes. For the most part, the writer is correct here in that Bonny is an admixture of people, and the political shift in the 17th - 18th century introduced the Canoe House system and feudal system into Bonny. However, since then, Ijaw houses have controlled the commerce, not "Ndoki". 8 Likes 1 Share |

Perhaps you misunderstand me. Well, now that I’ve provided all the context beforehand, let me restate my words in a more blunt and concise manner. The idea that speakers of a language are genetically related to the earliest speakers is not a guarantee we can make. The idea of a “super dialect” (proto language) is also a hypothesis that we generally cannot prove. So “super dialects” become reconciliatory tools (i.e. used to construct language family trees). In other words, the idea of a “super dialect” is not a guarantee that we can make. Your approach has similar foundational markers as the current orthodox teachings of the Igbo academia, which do not hold up to scrutiny; fundamental pitfalls, I call them. It will ultimately force one to take a different approach in their considerations. So with all that said, I was never making arguments to convince you to drop your approach. Instead, I wanted to understand why, despite all the pitfalls, you choose to stick to your guns. In a way we’ve come full circle, because I still hope for my original request to be answered. If you’ve got any novel information or considerations that informed your attempt to group the various lects, feel free to share it. In other words, what realizations did you come across? What insights do you have? What is it that truly informed your opinion so much so that you would want to take this approach and stick to the list of only three grouping despite all the pitfall and I had mentioned? That is ultimately what I’m interested in and all my words were to prompt you to share what you might have realized or seen that others (like the Igbo academia) might have missed. Because I would definitely like to know. However, it’s also understandable if this is just the beginning of your working theory, or a hunch. Often times, we start off with hunches. If you’re still at the “this is a hunch” phase and need to take time to flesh out your working theory so that you can comfortably explain it to others, then no problem. That’s normal, and I’m content to wait and see where your current line of thought takes you in the future. |

SlayerForever: This would have to be one point where we may just not agree. There are definitely levels to this and all we really do is paint a “general idea” at each level. Still, the potential to dive deeper, decompose the context and build an interpretation is worth the pursuit of “specifics”, even if speculative or hypothetical. SlayerForever: You don’t need to think hard or look far to gain a sense of this. Languages move due to various factors like cultural influence, diffusion, politics, etc. With these many factors the map of “speakers” of a given language can quickly become different from the map of said language’s earliest speakers. English is an excellent example of this. Despite the fact that westerners do not notably inhabit countries like Nigeria, these countries speak English. These countries invariably represent surviving speakers not related to the earliest speakers of English (excluding the fact that we are all human). As such, the language has a different spatial distribution from that of its earliest speakers. Now, let me provide you with a hypothetical. Say that the population that represents English’s earliest speakers are wiped out by say nuclear winter. This isn’t that far fetched. The US and other world powers have been at the brink of such a reality at least once. It is easy to imagine a scenario in which it was never abated. In such a case, the surviving speakers of English end up being those communities/countries to which English had been spread. And just like that, there are no surviving speakers that are related to the earliest speakers of English (as this population is wiped out). Now scale this down to hunter-gatherer populations that represented the societal structure of much of humanity for millennia. It is easy to wipe out a hunter-gatherer society. They can make the wrong move and end up in natural life-threatening situations of their own. They can be hunted and exterminated by another unrelated hunter-gatherer population. They could also be disadvantaged in the sense that they do not procreate quickly enough and their population declines until the last surviving member dies. None of this is hypothetical. We know this happened to these populations rather often. With this context established, it is easy to see how language can spread from one hunter-gatherer group to another for various reasons (contact, internal/external politics etc). It is also easy to imagine the society that initially spread it gets wiped out. The language itself can continue to spread (and innovate), but by that time, the surviving speakers do not represent the language’s earliest speakers. This is why I say that the further back in time we go, the more we lose any sort of guarantee that modern, surviving speakers are the same population as the language’s proto speakers. It simply is not a guarantee that we can make, no matter how we look at it. This is why I believe the approach by the Igbo academia has a fundamental pitfall. Only in instances where we can guarantee isolation and language innovation can we truly consider the possibility of surviving speakers being related to the earliest speakers. This is also why I hold the view that the idea of “proto-language” is reconciliatory. It’s is unlikely that there existed a group that spoke that reconstruction. Instead, it is more like an approximation used to reconcile the surviving lects of a given language. Long story short, a very general broad strokes list of three groupings based off non-guaranteed ancestral relationship (which may or may not match the language history of the area), is simply the same sort of pitfall that the academia has been holding on to for decades now. It is really hard to support such a theory without ignoring various lects and communities (which is exactly what the academia has done for decades). Lastly, a grouping of three is just not representative of the dynamics in the region. So those questions you claimed you were seeking answers to will likely not get answered with your current approach. You will have no choice but to dive deeper, become more granular and eventually add more to your list of dialect groupings. |

SlayerForever: What you’ve just described here is a hypothetical example of how dialect continua can be formed. According to linguists, dialect continua are typically formed when societies have an extended agrarian period. In other words, two or more language communities with agrarian lifestyles and occupying relatively contiguous territories for long enough will linguistically merge branches (eventually). What that “long enough” period looks like is dependent upon the societies in question; too many factors at play to make a blanket statement. That said, I believe your hypothesis is too “neat”, and if there is one thing about human history, it is far from neat. From my point of view, your hypothesis falls into the same sort of pitfall that the Igbo academia (linguists and historians, specifically) fell into; the assumption that we are working with a large “meta-language” whose speakers were all neatly related. I believe this assumption is likely due to the fact that some people still heavily associate the movement of language with the speakers of said language. However, how language diffuses and how populations move are not the same thing. They don’t always correlate. In fact, the farther back in time we go, the more we lose any sort of guarantee that the surviving speakers of a given language are in any way related to the speakers of the “proto language” (super dialect, if I could borrow your words). On top of that, the farther back in time we go, the more likely that the idea of a “proto language” (super dialect) is simply nothing more than an assumption we make to reconcile linguistic branching. Understanding that last point is critical. I don’t know if I made it clear enough, so let me know if I need to restate it better. Now, with all that context provided, here is the main point I want to make: “Igbo language” existing as dialect continuum implies that some sort of dialect leveling has already occurred. Such dialect leveling could be as insignificant as two or more already very close dialects become even more similar at their borders. It could also be as drastic as two or more different language communities merging branches at their borders. It could also be any manner of combinations between these two. Now with this range of possibility, a short list of dialect groupings based on perceived similarities (and hypothetical ancestry) will provide us with little to no novel insight into the past. Meaning we get our real insight from identifying the differences that often encode significant linguistic (and sometimes historical) information. These differences are essentially markers for identifying isoglosses. The more isoglosses we consistently can identify and validate, the better we position ourselves to paint an honest picture of the language (and perhaps cultural) history of the surviving communities. So if you really want to make headway in answering those questions you talked about earlier... i.e. the quote below: SlayerForever: You are going to need a more expansive list than just 1. Archetypical Anambra 2. Waawa 3. Southern Igbo |

SlayerForever: So what is the ancestry you hypothesized then? |

SlayerForever, Nairaland may not be the right place for you then. Granted, there are still a handful of us here that actively engage in the sort of topic you are referring to. If you search for AjaanaOka and my own handle (ChinenyeN) on Nairaland, you should be able to find a number of threads where we discuss many different topics within this same domain that you are talking about. Most people, however, do not touch this sort of topic, but I believe many of them are interested. They just don’t know how they can contribute to it, so they will more eagerly follow threads where others are discussing things. SlayerForever: I see. Now I am understanding your three-group listing better (or at least, I believe I am better understanding what has informed it). This is obviously a loaded question, but I don’t mind diving into it with you. So let’s start with what we see. You’ve presented a list of three categories that you believe characterizes all surviving lects. You’ve also just recently shared that you are looking beyond lexicology in building this list. Now, do you mind sharing some specifics on the things beyond lexicology that informed your listing? 1 Like |

I’m a bit confused on why you’ll state that your grouping is not based on an in-depth study, then ask what others think (all of whom have disagreed), yet you disagree with them all. So on what basis are you disagreeing? Was your grouping actually based on an a deeper study? If so, why hide that? If you’ve got any novel information or considerations that informed your attempt to group the various lects, feel free to share it. I don’t know about most, but I know there are at least a handful of NL’ders that would be interested in learning how, why and what informed your grouping. 1 Like |

SlayerForever: No, they would not actually. As a case-in-point, the sound shifts that have come to characterize the “Anambra-Imo” dichotomy (the Isogloss A vs B) are often not applicable to the Afikpo, Alayi, Aro axis. There’s actually even more variety of shifts within this axis than in the well-known “Anambra-Imo” dichotomy, so you would need at least an additional isogloss to sufficiently characterize some of these lects. SlayerForever: Yes, and there is such a thing as insufficient. A set of parameters that only defines two or three “main dialect groups” is insufficient for delineating all surviving lects. 1 Like |

That is an oversimplification. So I’ll ultimately say it’s unfounded. Here is the truth. There are two major isoglosses. We will call them Isogloss-A and Isogloss-B; A & B for short. They are characterized by the following features: 1. Switch between h/r. A uses h, B uses r. 2. Switch between r/l. A uses r, B uses l. 3. Switch between h/f. A uses h, B uses f. 4. Switch between l/n. A uses l, B uses n. Due to the the fact that the idea of “Igbo” is hyper focused on Anambra primarily and then Imo secondarily, the impression now exists that this isogloss dichotomy is an Anambra-Imo thing. By effect, it is treated as a “Northern Igbo”-“Southern Igbo” thing. This is far from the truth and the picture is more complex. There are are communities in A that use f and not h (with regards to this switching). There are communities in B that use h and not r (with regards to this switching). Long story short, these two isoglosses are not sufficient enough to characterize all existing lects. Likewise, an “isogloss list” that separates Waawa, but does not separate the old Bende group of lects is not well-put-together. So no. Igbo cannot be separated into only three major lectal groups. We will need more than that to fully characterize and delineate all the surviving lects. 2 Likes |

AjaanaOka: Ahh. I see... and I guess it it prompting you to reconsider the hypothesis due to the potential difficulty of reconciling the Ikpachor lect as the lect that survived to become Ekpeye. After all, the Ikpachor would not have been isolated and so their lect should also have been caught in the continuum. If indeed the Ikpachor language survived the Akalaka migration, then it might stand to reason that Ekpeye would have a higher degree of mutual intelligibility with the rest of Igbo. Or something to that effect. I think I can understand better now how our conversation would go against this hypothesis in some way. There is still merit to your hypothesis in some aspects. What you consider as a potential knock-off of Aboh-induced migrations is actually acknowledged by some communities. There are definitely communities in the southern stretch (sprinkled through Ikwerre region and into the lower part of Echie) that claim a migration specifically from the Ndoni region. I don’t know when those migrations could be dated. I did not try looking into it, but perhaps at least some of them could be related to this event. So there’s definitely something to be explored here. Who knows if it might even upend some of our conversation up to this point. Thanks for taking the time to share it. 1 Like |

letu: I have actually looked into this. I have dubbed this pattern of naming settlements as “dual-naming”. It is very common in the central Igbo area, but could not determine a corresponding pattern on the Ngwa side of Imo. Most Ngwa communities do not have follow a dual naming, and in communities that do have some sort of dual naming, the “Ezi” and “Ihite” name is not used. For instance, we have Oria la Uga in Ntigha, Ezi la Ife in Ndeakata, and Osi la Oji in Amavo, just to make a few. But it does not seem to be the same thing as the “Ezi na Ihite” pattern found in central Igbo”. There are several Ihie’s in Ngwa (around at least 5), but none that I know of have claimed to go by any other name that uses “Ezi”. So for the time being, I considered that the “Ezi na Ihite” pattern is not a feature of ancient Ngwa settlements. The closest to “Ezi na Ihite” that we have in the area is with Mbaise. Yet, even with the case of Mbaise, the “Ehi la Ihite” (how they say Ezi na Ihite in the local dialect) seems recent, because it seems there was a different expression used; Ohuhu la Avuvu. This is something I have been meaning to dig into a bit more. I have not been able to speculate on when/how the area could have come to be known as Ezinihite, as I have not yet been informed of any oral traditions that speak about it. Perhaps I should pick back up on that research soon. |

AjaanaOka My working chronology for Ngwa expansion Nfulala; Pre-WADP (West African Dry Period); Pre-1000s The stretch of communities from Ahiara (north-central Mbaise) to Nsulu (north-eastern Ngwa) constituted a large block of autochthonous communities. They do not acknowledge a single common ancestor, and save for a few short distance migrations in this contiguous space, the communities claim to have originated in their current location; what is locally called "Nfulala". Based off my working chronology, I presume that many of these communities had developed into clans of their own by this period (before the Little Ice Age). They may share claims of kinship with one or two other clans and share common tutelary and ritual aspects (though often times without the memory of a common ancestor). However, the idea of a unifying name for these communities did not exist. For instance, Oboama and Umunama in south-central Mbaise acknowledge kinship but don't recall the name of their common ancestor. The set of ten loosely integrated villages (or village-groups?) in north-western Mbaise (Ahiara) mention a common ancestor, but no idea where he came from. Aside from the "Imo" legend, the Ukwu clan in northern Ngwa does not have traditions that acknowledge any "brothers" among the surrounding communities, and just as with Ahiara, the Ukwu group acknowledges a single common ancestor among themselves but with no statement of where he may have come from. Nsulu and Ntigha (northern and north-eastern Ngwa are two large groups that do not have any memory of a common ancestor, but acknowledge that they are brothers. There is also the claim that they are from the Ukwu group, but the Ukwu group claims to be unaware of a migration. I could go on, but I'll assume the context is relatively clear. I gave this a dating of pre-1000s for two reasons: 1. I have no idea how long this period lasted. I am aware of an incident where archeological artifacts that were discovered in the area dating to 9th century B.C. Memory of anything beyond the current modern composition of village-groups is lost. So it’s difficult to speculate on the dynamics pre-1000s outside of general things like “being an Iron Age society”. 2. It gives enough of a distance in time that I believe is reasonable to account for the adoption of "Ngwa" as an ethnonym. It is well-established that the "Ngwa" ethnonym is tied to the development of the Imo, but the communities claim to have been living in the area while the river was still a shallow stream, and the original course of the Imo (according to Oboama Umunama, Ubahi, etc.) ran elsewhere. These communities acknowledge the existence of the other groups at this time, affirming the existence of this autochthonous stretch and affirming the lack of an “Ngwa people”. Expansion During the WADP; 1000 - 1400 Initially, I had assumed the area shared a related set of traditions that encoded the event of the Imo, but after our conversation some time ago about the Little Ice Age, I shifted the the point of my focus and started doing more digging, research and interviewing. It turns out there are traditions that encode the memory of early long-distance movements during periods of dryness. This has led me to consider these early expansions as potentially distinct from the massive and more well-known "waves" that are associated with the academia's current understanding of Ngwa migrations. From what I gathered, there are communities in the southernmost parts of Ngwa, like Ihie, Obokwe, and even Ohuru (in Asa) and Umuagbai (in Ndoki) that are part of this early population dynamic. For the working chronology, placing this event within the early phases of the WADP made the most sense for a few reasons. 1. Some of the Ngwa communities in this axis have traditions that assert their movement while the Imo was still shallow. This suggest the the river beheading event had not yet occurred. 2a. There are two kinds of ofo I want to contrast. The lineage ofo and the Ngwa clan ofo (known as Ofo Asoto). When someone migrates and establishes a new compound or community, they can also (or in effect, they also) establish a new lineage ofo. You can consider this as a system of deriving ancestral authority between communities. 2b. Now that I've established that context, I'll continue. Southern Ngwa communities do not possess any of the Ofo Asoto that are claimed to have been created and distributed when the Ngwa clan consciousness was birthed. There also exist no derivatives for the Ofo Asoto, unlike the lineage ofo. This suggests to me that there were some early southern expansion prior to the development of Ngwa clan consciousness. 3. It is generally thought that Ngwa expansion occurred in large, condensed waves. The expansions that birthed southern Ngwa communities like Ihie, Obokwe and Ohuru (among others) are also grouped into this. However, when I considered these groups' traditions, the sort of single-track idea that Ngwa chronology can be characterized by a fluid series of large population expansions (within a short span of time) did not make sense. It did not make sense that a period associated with the Ngwa's greatest population boom would also be associated with a dry period that would have limited population growth. But something else does; the wet interlude. With this in mind, I decided to associate early southern movements with the first phase of the WADP and effectively separate them for the more well-known large population expansions. 4. As part of the working chronology, I concluded that the expansion from Umuagbai into Igolo Oma might have likely occurred prior to the wet interlude. So I included the expansion of Bonny here. However, there is also a secondary larger expansion during the middle/late part of the Portuguese era that brought additional Ngwa into Bonny and established Igwe Nga, present day Ikot Abasi (not Opobo). By my chronological estimates, early Ngwa contact with Asa occurred in this time, and it is likely the case that the Asa did not get too far in before making contact with some early Ngwa. To illustrate, the Ipu and Oza claim a west-to-east migration up to the point where their trajectory turns acutely south to north. As we’ve demonstrated earlier already, spacial distributions can tend to change flow when faced with an obstruction in their path or when crossing streams. Save for Ohambele and the Ibeme, Asa communities spacial distribution from Obigbo is almost 100% in a northerly direction. This breaks their west to east flow which they should have been free to continue, if we believe the claim that they inhabited the area up to the 17th century without Ngwa contact. So I suspect early contact occurred at this time, which gave birth to the Asa ethnonym. Then a later, larger wave of contact occurred after an Ngwa identity had become firmly established and this is what is remembered. The Wet Interlude & the beginning of an Ngwa identity; 1400 - 1500 As part of my working chronology, the first of my considerations is that the first half the WADP saw the decimation of previous bodies of water that cut deeper into the western part of Mbaise. The wet interlude seemed to me like a good candidate for explaining both the sudden the development of the Imo river and the development of an Ngwa identity. I placed the time frame between 1400 and 1500 for three reasons, mainly: 1. It is my suspicion that this period is responsible for birthing the infamous Imo legends. No other time period makes sense when I consider the environmental aspects of the development of the Imo. The impact on oral traditions further supports this. Miri Ojii (the stream that used to be there before the Imo) is said to have so quick and so exponentially overflowed its bank. Prior to having knowledge of the Little Ice Age, I always assumed that this event spanned the course of at least a few generations (perhaps a century or more), because oral traditions have the habit of condensing time. However, knowledge of the Little Ice Age makes it more believable now that the event happened within a much shorter timespan than I initially imagined, and it would explain why it had such a profound impact in the area that it became heavily encoded into oral tradition. A river beheading that takes 100+ years would likely not have had the same impact. The previous dryness coupled with the sudden surge of a new river though makes sense, and I can see how this can happen within a generation or two (unlike the four generations I conceived of years ago). 2. The impact on the way of way of life or the local communities. I put this within the 1400 - 1500 to overlap the event with the end of the first half of the WADP and the early part of the wet interlude. I wanted to see if I could use it to reconcile some details about the way of life of the communities. For the local communities, the ethnonyms that came surfaced with the Imo legend were "Ngwa Ohnuhnu" (for the fact that villages on the western bank engaged in roasting their yam) and "Ngwa Nzem" (for the fact that village on the eastern bank were considered lucky by their counterparts on the western side of Imo). I alway used to ask myself what was the basis for this dichotomy. Why would Mbaise need to adopt the practice of roasting? And why would Ngwa be considered lucky? With the WADP in mind, I considered that the impact of the drought could have been severe enough that water scarcity prevented the practice of boiling yam. In contrast, oral traditions encodes the idea that villages on the eastern bank boiled their yams, potentially indicating that the region of their settlement saw better relief from the dryness than their western counterparts. It's difficult to really say why this is the case other than the established worldview that "Ngwaland" is considered highly arable, compared to Mbaise which has far less arable land. Whichever the real case, the dichotomy between "Ngwa Nzem" and "Ngwa Ohnuhnu" was born. 3. The final reason for why I placed this time frame between 1400 and 1500 is to account for the Iwhnerneohna wave of migration. According to Ngwa oral traditions, Igwuocha is settled by them in a migration led by an Ngwa hunter. According to the Etche, Ngwa presence (both "Ngwa Ohnuhnu" and "Ngwa Nzem" ) is already noted in the region before the establishment of Umunneoha. According to the Okrika, the movement of the Obio (in Ikwerre) can be placed at around late 1600s/early 1700s. Finally, the Obio acknowledge the tradition of "Ngwa Gbaka" and "Ngwa Owhnuhnu". Okrika’s placing of the Obio in PH by the late 1600s/early 1700s presented some dating complications. I initially had a later date for the development of Ngwa clan consciousness, but I decided to shift it to 1400 - 1500 as an overlap between the WADP and the interlude. It allowed (what I believed would be) a reasonable amount of time for the internal dynamics between Ukwu and Umuoha group to play out and establish the defining events in Ngwa clan history that would then allow me to reconcile Obio’s use of “Ngwa Gbaka” which is different from the original “Ngwa Nzem”. The Formation of the Ngwa Clan Identity; 1500 We are finally at the point where my working chronology meets up with the academia. The academia has struggled in defining when exactly Ngwa clan consciousness developed. Based on my chronology, I estimate it developed in the 16th century. I used to always wonder about this era in Ngwa history because it seemed so very condensed. In oral tradition, this period is told as though it occurred before the expansions. I guess in a way it did, but it’s also recounted as the “founding period” in which northern Ngwa is settled and everyone else expands from there, but that isn’t quite the case. I’ll reiterate briefly as a refresher. The stretch of communities from Ahiara to Nsulu represent nfulala. Sharing no memory of a common ancestor, but having traditions that may link them with one or more others communities within this stretch. The events that finally culminated in the development of the Imo reshaped the identities a bit. Communities like Ukwu (who as mentioned before had no traditions of acknowledging any “brothers”) became "brothers" with Umuoha and Avosi. Umuoha "lost" its brotherhood with Obizi (in Mbaise) on the West side of Imo (though Umuoha and Obizi do not acknowledge a common ancestor, they do acknowledge kinship). Onye Ukwu assumed the position of seniority, Nwoha became his “junior brother” and Avosi their “younger brother”. The story then became that these three brothers first settled at the Okpuala village in Ukwu group before dispersing to their current village groups. One other variant of this story is that there were actually eight brothers; Ukwu, Nwoha and Avosi from one mother, Nsulu and Nte (Ntigha) from another. Ngwu (Ovungwu) and Okwu (Ovokwu) from yet another mother, and Ntu (Mbutu) as a son of Nwoha. Yet another variant of the story has it that Ukwu, Nwoha and Avosi were the three brothers. They settled at Okpuala in Ukwu and Nwoha and Avosi moved out to establish their own village-groups. Nwoha has seven sons, three of which were Ntu, Ngwu and Okwu, who founded Mbutu, Ovungwu and Ovokwu respectively. Nsulu and Nte were apparently from Okpuala in Ukwu as well and moved out to establish their own village-groups. In reality these changes in the story don’t actually reflect kinship, but rather the internal civil conflict that occurred shortly after the development of the Imo. In short, the Ukwu group (which had assumed seniority and authority) got into conflict with the Umuoha group. The various stories I shared above reflect the sides that were drawn during that conflict. The Nsulu and Ntigha groups sided with Ukwu group. The Mbutu, Ovungwu and Ovokwu groups sided with the Umuoha group. The Umuoha group were essentially branded as separatists, undermining the self-ascribed seniority and authority of the Ukwu group. The conflict is stated to have gotten so serious that a truce of sorts was needed. A meeting was called for the village heads of these eight groups, and this became the defining moment in Ngwa clan history. The Ofo Asoto were christened and given to the eight village heads. The Nkpe constitution and ritual was instituted along with the Ala Ngwa deity. Okpuala-Ngwa in Ukwu group officially became the clan cultural capital, and from this point forward the Ukwu group adopted “Ngwa” into their ethnonym to become “Ngwa Ukwu”. The tradition shifted from “Ngwa Nzem” and “Ngwa Ohnuhnu” to “Ngwa Ukwu” and “Ngwa Ohnuhnu”. The idea of Ngwa as we know it today starts here. The Large almost Fluid Population Expansions; 1600 - 1800 This is the point where I may finally give some credit to the Asa 17th century claim, and as I said earlier, it’s interesting that I arrived independently on a similar conclusion. The difference is that I believe the 17th century dating only sufficiently accounts for those communities that disbursed after the resolution of the Ukwu and Umuoha conflict in northern Ngwa. For instance, it is well-acknowledged in Ngwa oral traditions that Igwe Nga, Igolo Oma and several other communities within the Asa/Ndoki axis are Ngwa, but these communities (including some in southern and eastern Ngwa) do not reference the “Ngwa Ukwu” and “Ngwa Ohnuhnu” traditions, suggesting dispersal prior to this defining moment. On the other hand, Iwhnerneohna (Obio) acknowledges the tradition of “Ngwa Gbaka” and “Ngwa Owhnuhnu”. In fact, the use of “Gbaka” (i.e. Imo/Ukwu) is telling. It shows that the Iwhnerneohna movement likely occurred after the shift in traditions from “Ngwa Nzem” to “Ngwa Ukwu”. Anyhow, this is also the point where we can see alignment between my working chronology and some of the known works in the academia. The large waves that gave birth to the large Ngwaukwu-Ugwunagbo village-group occurred at this time. The Aba la Ohazu settled around this time as well. Eastern Ngwa also saw an influx of post-conflict Ngwa people. Expansion northwards and northwestward also occurred helping to people communities like Obowu and Umuahia. In a way, they somewhat overrun the communities that were part of earlier expansions. Modern Ngwa; 1880 - Present The British arrived and made ethnic borders more rigid and the Ngwa body currently consists of the seven LGAs in Abia. 4 Likes |

AjaanaOka Regarding the explanation you provided on how our discussion prompted your re-thinking... I'd very much like to hear more about your "neat" explanation for the Akalaka movement. If for nothing else, then just out of curiosity. Regarding the Benin claims for Asa... As it turns out, there are hardly any intelligence reports written on Asa. I have not come across any, and historians like Oriji have noted that hardly anything was written about them during the colonial period. Only one author I know of (Nwaguru) cited an intelligence report from 1920, but I have not been able to source a copy from anywhere. There is though some documentation from the Native Court era. In 1927, J. Jackson wrote an assessment report on the Asa Native Court area. In it, he stated that based of the local claims, the villages can be grouped into two "origin" groups; those who claim to have come "from Ikwerre" and those who claim to have come "from Ngwa". Benin was supposedly not mentioned in this assessment report, neither was the claim of being "from Benin". That said, it is always possible that such detail could have been inadvertently (unintentionally) eclipsed due to the fact that the Asa are so "obviously Igbo". If anyone were to ask my opinion, I would say that there are a few things we can consider. The "Asa homeland" is claimed to be in the vicinity of Obigbo. Recently (since the 1970s), we've seen a common trend of "from Benin" within the stretch of Ekpeye to Obigbo. In one way or another, various wards or compounds within the communities in this stretch tell of a "from Benin" migration. I would say that it is very possible that those wards migrated with and/or settled among the Ipu and Oza. The current socio-political mood in southern Nigeria has made it possible to use these stories as anchors to further the traditions of Benin origin and/or migration. As for actual “from Benin” claims in the Ngwa/Asa/Ndoki axis, it is really only the Umueze (Ndoki) that have a definitive tradition of Benin migration that was shared with colonial administration. Umueze is also the only community with a clear early history of Ijaw relationship and a Central Delta migration claim. However, they also are recent settlers in the area, having arrived in the late 18th century. But now that Umuokobo, Ohanku, Ohambele, etc. constitute a clan alongside the Umueze (i.e. they are all now Ndoki), it is easy to see how (as time goes by in the reconciliation of a clan identity) both the traditions of Benin migration and the traditions of Ijaw relationship can also be adopted by these communities alongside their pre-existing traditions. So long story short, while I have not read any intelligence reports where the Ipu and Oza stated that they come from Benin, I do not think it far fetched to at least expect individual or some collective compounds and wards that do have such a tradition within Asa. As for the 17th century dating provided in that article that Igboid shared, to make a long story short, I would certainly say it is too late of a date, especially if we want to believe the Ngwa traditions that claim they expanded to "Igolo Oma" before Bonny became a kingdom. In fact, we can ignore the Ngwa traditions regarding Igolo Oma, focus on the traditions of Bonny itself and still get an earlier approximation than the 17th century. Alagoa and Fombo note in their research of Ijaw traditions that the account with respect to Bonny acknowledges Ijaw sojourning among Ngwa (in what is now Ndokiland) prior to the Ijaw expanding to Bonny. If the Ijaw expansion into Bonny occurred that that 14th/15th century timespan, it suggest Ngwa expanded from their own “homeland” long before the 17th century. However, to make a long story long... In a way, I do agree with that 17th century dating, it actually matches up with one aspect of the working chronology I have. I’ll demonstrate how/why later. Yes, after all these many years, I finally do have a working chronology, thanks in large part to you and the culmination of all our discourse over the years. I’ll share it in the next post. Of course, it is just a working chronology and always stands to be revisited in light of new information. I’ll provide the details of the working chronology below, and I can expand on particular parts of it as well if you want. The following comes from attempts at examining the traditions of various Igbo-speaking and non-Igbo speaking groups in the area. Also, to be 100% transparent, I have completely thrown out the Umunneoha tradition of origin that has become so popular both among the academia and within Ngwa circles. I have thrown it out is due to the following reasons: 1. Accounts of events pre and post Imo from groups within the Ngwa side of the Imo 2. The entirety of Mbaise, which many Ngwa communities claim to share affinity, recognize the existence of Ngwa on the east side of the Imo, pre-Isuama. Mbaise also does not acknowledge a migration origin from Isuama. 3. We have established here on NL numerous times that Jones & Forde’s reconstruction of dispersion within Igboland (and the “homeland hypothesis” that developed from it) only sufficiently explains Isu/Isuama movements. 4. Jones & Forde’s assertion that the Ngwa came from Orlu is based off the claims of some known villages in Ngwa that remember migrating from Amaigbo or the Amaigbo axis. These communities traditions do not reflect the traditions of founding settlements (typically known as Okpuala) within the Ngwa. 5. The claim of migrating from Umunneoha actually first surfaced in 1973 in Nwaguru’s book. Nwaguru was Ngwa and he himself believed in the central homeland hypothesis and sought to reconcile Ngwa traditions with the hypothesis. He did so by furthering Jones & Forde’s misinterpretation of the Imo legend. The Imo legend was never a tradition of origin (in the sense of a migration). Rather, it only served to affirm kinship with Mbaise and establish the time from when Ngwa clan identity began. It was a response to the sudden environmental changes at that time. 1 Like |

Actually, thanks for bringing this up, Igboid. It triggered something in my mind. AjaanaOka, this might be of interest to you with respect to proto-Lower Cross and proto-Igbo merging. Ndoki (Umueze) and Asa (Ipu and Oza) do not have an in situ tradition and share the memory of a west-east (and in the case of Asa, south-north) migration (much like Ohafia and Item, etc.). Some people within these communities actually have a Benin story (Umueze, Ipu, Oza), some only mention migrating from the Ikwerre area (Ipu, Oza), some mention migrating in the company of Ijaw (Umueze). Whichever the case, Asa and Ndoki either migrated from or through the Ikwerre area to get to their present location, and there is evidence of some affinity in their lects. With this context, I am trying to wrap my mind around one particular thing; the use of "teete" (father) in Asa and Ndoki (this time, Umueze and other communities like Ohambele, and by extension Ibeme in Ngwa). Their use of "teete" is obviously a cognate of proto-Lower Cross word for father. Whether this is a loan or not is not my main concern. It most likely is, but it has been incorporated rather well (and dynamically) into their lects as opposed to being static in its usage (as may sometimes be characteristic of loan words). teete (father) teetekwu (grandfather) nwate (kinsman) In fact, I'm not so much fascinated with the use of "teete" as I am with the level of adoption it has had, suggesting it's active use within their speech communities for quite some time. If we factor in the stretch from Ndoki to Ekpeye, we have more variety of terminology for "father" than anywhere else in the Igbo-speaking region. There is also some similarities with respect to reduplication, i.e. teete, didi, etc. that I have not noticed among other speech form (but I guess this isn't saying much since I cannot claim to be versed in every Igbo speech form). Anyhow, your thoughts on how a supposed crossing of streams between proto-Lower Cross (at least) and proto-Igbo could have blunted the spacial distribution of Igboid branches might very well have a real basis. There is evidently significant branching within the southern strip of Igbo-speaking communities, whether it be from standalone proto-Igboid branches, or a yet unknown cross-stream event (or series of events) between proto-Igboid and proto-Lower Cross (at least), or even both. Establishing relative dating for all of this will be a different story, however. |

AjaanaOka: A few things to note about this that might make this plausible. Now, if we casually look at their oral traditions, there is the claim of migration from outside what we currently know as “Igboland” (current modern, political definition). Some like Abiriba and Aro coming from deeper into Cross Rivers territory. Others like Ohafia, Item etc coming from what is now Rivers state, wrapping around Obolo and migrating northeastward. If we casually examine the linguistic features of these communities, we can immediately tell that their linguistic branches are part of the dialect continuum. It stands to reason that their linguistic ancestors had to have been in the area for quite some time (as with the rest of the older pockets of proto-Igboid branches) and got caught up in the continuum. If so, it then suggest a deeper easterly extension of proto-Igboid branches into what is now Cross Rivers (in the case of communities like Abiriba and Aro). It also supports the idea of linguistic merging for southern proto-Igboid branches and proto-Lower Cross (if not proto-Cross Rivers itself). And yes, if we conceptualize it more like streams (the way your west to east hypothesis generates sensible waves), then it seem plausible. 1 Like |

AjaanaOka: Please do try it with your own lect. I’d definitely like to see it. AjaanaOka: Sorry, but do you mind expanding on/clarifying this part for me a bit more. I understand the aspects of the discussion with your Ika friend, but I am not sure I follow the last part about how/why our current conversation is prompting you to revisit your working theories. AjaanaOka: Interesting, perhaps I might search along with you then. Maybe one of us will eventually get luckily and we can share the findings with the other. |

ChinenyeN: Honestly, thinking about it now, we can do this work ourselves thanks to the efforts already made by Williamson and Ohiri-Aniche to provide a comparative wordlist. Decent maps of Igboland already exist. We can just map out the dialects used in Williamson and Ohiri-Aniche's comparative Igboid wordlist and work to identify major isoglosses using the wordlist and other linguistic information. I might be able to start it this weekend. 1 Like |

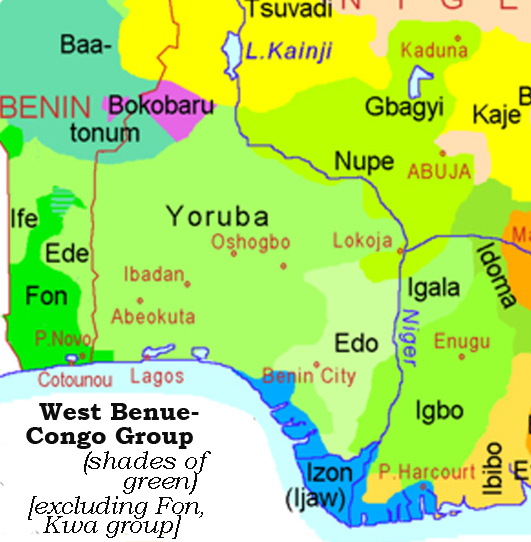

Here is the link to Clark’s comparative Ekpeye-Ogba-Ikwerre work in PDF. https://www.dropbox.com/s/lkzjylv8oybfwyk/3f84491c623efa45c3e3879c7f1fbf3e.pdf?dl=0 And my comparative addition with Ngwa: https://www.dropbox.com/s/yjmt33gtue85m5r/100%20Wordlist.pdf?dl=0 So I spent the weekend reading through Jacob Oludare Fadoro’s comparative Akokoid wordlist. Sure it may not be enough time to fully digest it and develop a thorough opinion with respect to how it relates with the Igboid context, but something did strike me while reading it; the conclusion where he mentions dialect continuum. The dialect continuum part reminded me of having read somewhere (I forget where) that (i) dialect continua result from linguistic branches merging into each other and that (ii) such merging is typically made possible when populations become sedentary or agrarian, giving innovations the opportunity to ripple and have more lasting effects. If we work backward from this logic, we can infer the likely existence of multiple proto-Igbo branches in the region. Working Backwards (ii) Contrary to the picture painted by current Igbo academia, the key features that are used to define the “homeland” (i.e. dense communities & nfulala traditions) exist outside of the “homeland”. Pockets of independent, agrarian dense populations existed within the Igbo-speaking region for quite a long time (as can be affirmed by the traditions of numerous communities). (i) Creating a language family hierarchy apparently doesn’t make sense for a dialect continuum, most likely because we cannot consistently replicate cognate scores enough to differentiate branches. Rather, we need to rely on qualitatively examining cognates as well as other linguistic features to create demarcations. If we are lucky, those demarcations could be looked at as being akin to echoes of long-dead genetic branches, and in my non-professional analysis of some linguistic features, I believe that there is a definite isogloss that spans the entire southern belt, leading me to believe it is the remnants of perhaps a couple, genetically related proto-Igbo branches in the region. I know I’ve expressed this before, but still, this is why I am so disappointed in the Igbo academia at times. I feel that (aside from the Roger Blench documents), no real effort by the academia have been made to advance the study of the isoglosses in the region. They’re so content with the hinterland homeland hypothesis. Now, I want to show you something. I don’t know if you’ve seen this before or not, but I was reading through some websites I saved when I was researching the Niger-Benue confluence. This is an image from one of them.  I personally find this next part that I am about to dive into a bit exciting, especially when we take into consideration your eastward movement hypothesis. The key area I want you to focus on is the curved border between Igbo and Ibibio. Now, here is a free drawn flow diagram by me to represent the hinterland homeland hypothesis. [img] https://i.ibb.co/6XYhL2Z/2-C6-FC8-CA-662-E-4-F28-8-DB1-8-A8-D61128-B40.jpg[/img] And here is another to generalize and represent your southern entry hypothesis. [img]https://i.ibb.co/q1yFJYQ/9-EA2-B6-D0-5-D6-C-49-FA-AA51-8-CFD237-CB660.jpg[/img] * I don't know why NL isn't showing these images correctly. Sigh. This is annoying. I guess you may need to open these links in another tab, because they really help illustrate the point. After actually drawing this out, I started becoming a bit more convinced of your southern entry hypothesis. Compared to the hinterland homeland hypothesis, which seems to work against a flow, yours presents a curious and sensible set of waves. Even though we are only just speculating on cognate relationships with Lower Cross, a west to east push as visualized on the map still seems plausible. By the way, if you want the link to the site where I pulled the image, you can view it here: https://amightytree.org/niger-congo-languages-and-history/ Now, I’m going to take some liberties and dive into some speculations here. Recall my statement from earlier, that relatively dense populations typically force incoming communities and to settle around them. I wonder if, in a way, we could observe this same behavior with language innovations. There is a theme of east to west movement on the part of the Lower Cross and Central Delta families. With their eastward expansion blocked by Bantu-speaking communities, pioneers of proto-Cross Rivers perhaps could have ended up further west (in or near the vicinity of proto-Igbo). Of course, this would have been some time before the more recent mass migrations of Central Delta and Lower Cross. Long story short, if we consider the flow pattern of surrounding spatial distributions for other language families such as the Cross Rivers, Edoid and Yoruboid, a west to east wave for Igboid makes sense. And it just hit me now! If we attempt to draw demarcating lines for various major isoglosses in the Igbo-speaking region, I would not be surprised if our lines cut and striate more horizontally (indicating west to east expansion) than vertically (indicating north to south expansion).  Our linguists need to get on top of this ASAP. Our linguists need to get on top of this ASAP. I might say one thing though, considering Ekpeye in all of this. It is of course without a doubt that Ekpeye is an Igboid lect, but Ekpeye did not get caught up in the continuum as other lects did. If we assume that Ekpeye is old (as in an older Igboid branch), then there is the possibility that the Ekpeye branch is a later arrival into the Igbo-speaking region compared to other Igboid branches. If this is the case, it would do two major things for the southern entry speculation. 1. It affirms the antiquity of the southern belt. The fact there existed an older, surviving Igboid lect outside of the continuum that shows high affinity with the southern belt isogloss speaks volumes for our speculative southern entry hypothesis. 2. If the Ekpeye branch is indeed a later arrival into the region, then it would imply that up until relatively recent history, there were in fact pockets of Igboid lects existing outside of the continuum, further west towards Ondo. Ekpeye just so happens to be the only surviving member and the rest were not dense enough to force incoming Edoid waves to wrap around them... .. because the bulk of the Igboid branches had already long since shifted further east. #2 reconciles my concerns with the current spatial distribution of Igboid lects. Also, Benin had an expansionist monarch era for quite some time. If indeed your west to east expansion is on the right track, then the expansionist Edoid period provides a confounding factor which further reconciles my concerns about the lack of surviving Igboid groups outside of the Igbo-speaking region. AjaanaOka, my friend. I’ve started coming around to your southern entry hypothesis. Granted, all I am doing is speculating here, but it the speculative support and conclusion is growing on me. 1 Like |

AjaanaOka: It's taken a little longer to get my thoughts together before I respond. So I'll leave this bit while I continue my research and gather my thoughts. I will actually try to make this one brief as opposed to my last post where I might have ran on for too long. I'll pose it more so as a thought exercise, and give you time to also think about it. Essentially, I am interested in two things: 1. Based off the currently accepted classification for the Lower Cross languages, what might we be able to estimate their branching and getting a sense of potential timing for proto-Igboid and proto-Lower Cross interaction in pre-history. 2. Reconstructions. I may need to do some digging into Igboid reconstruction and Lower Cross and Central Delta reconstructions and see what linguists have identified as potential loans (taken from Lower Cross/Central Delta). Ultimately, I wanted to get a general sense of whether or not we can reasonably speculate on early interaction. The reason why is because I do not quite feel so convinced on this front. Personally, I see this Lower Cross component as key to providing reasonable support for a southern entry, but only if we can reconcile it. If we cannot effectively justify it, then it leaves me wondering if we have no choice but to accept that the southern entry likely only accounts for a yet unidentified proto-Igboid branch (or branches), while other branches potentially had other multiple (perhaps isolated) points of entry. BUT, if your speculation is right that various words that are ubiquitous across surviving Igboid lects point to pre-historical interaction with Lower Cross ancestor languages, then we end up with a significant discrepancy. Lots to think about. |

AjaanaOka: I don't know if this is the same wordlist, but I also have one for Ekpeye, Ogba and Ikwerre from one of David Clark's works. I was using it to fill in Ngwa counterparts so that I could attempt to calculate (as a hobbyist) Ngwa's lexical similarity relative to the other three, but never finished doing that. I got distracted with other things, but I guess this weekend I might try and continue where I left off. I have a screenshot of part of it somewhere. I can dig it up or just take a new screenshot of it, if you'd like to see it. I have it stored in a Google spreadsheet so it will be easy to find. AjaanaOka: When people make this sort of population vs age argument, I typically find that they don't quite grasp the nuances of language families and branching relative to population movements. For me, your last paragraph is very plausible. Ever since I learned about Ekpeye and learned more about their lect, I became increasingly convinced that they are the last surviving speakers of a branch that most (if not all) of the southern communities once belonged to; just from the knowledge I have concerning a couple of grammatical features of Ngwa that are considered "archaic" by modern Ngwa speakers. |

I wonder if the OP is referring to the Nmaji/Njoku cultural practice. I'll expand on that. Worst case scenario, I am wrong and this is not what you are looking for @OP, so you can feel free to ignore it. Best case scenario, this is exactly the information you seek. I'll leave that for the future to determine, since I don't know. Anyhow, Nmaji is part of the agricultural practice of Ngwa and Mbaise (at least, I'm sure of these communities -- I cannot speak for all others). It's literal meaning is "knife of the yam". Nmaji is the female counterpart of Njoku. Both are dedicated to Ahinjoku. The practice had a number of different implications and some of it varied from community to community. Some communities used to use the skulls of dead Nmaji and Njoku as totems for worship. While alive, it was thought that the Njoku and Nmaji had claims to yams of their choice from people's barns. It was thought that to allow the head of an Njoku or an Nmaji to touch the ground was effrontry to Ala and would invite her punishment. Any attempt to prevent them from asserting such a claim was disrespectful to both Ahinjoku and Ala. In essence, the Nmaji/Njoku culture was sort of like a fertility cult, centered around yam, Ahinjoku and Ala. For example, anywhere they co-occur (an Nmaji and Njoku that acknowledge each other's existence), they were effectively considered as married. No one could make any claims on the bride wealth of the Nmaji except for the Njoku in question. But if they ended up not marrying each other, they would at least marry a different Njoku and Nmaji respectively. Nmaji and Njoku are high status symbols within the cultural region. There's no need for me to dive any deeper than this since I am not certain it is what you are looking for. If it is, then hopefully I've said enough to get you going on your research to learn more about it. 2 Likes |

AjaanaOka: Ahhh. This has provided much needed context. Thank you. AjaanaOka: This exception is exactly the reason for my question. I see though that you have some additional statements on this later in the post, so I'll respond further down in this post. AjaanaOka: I think I will combine my response to this with below for ease. AjaanaOka: Now this (the bolded) is indeed interesting. I assume these are cognate scores. If not for these two bolded items, I might have remained largely unconvinced. But allow me to back up a bit and explain my thought process for context. I am certainly in favor of the general premise (being southern entry into the Igbo-speaking area). I was just still trying to grasp the Edo-Ondo borderlands part of the speculation. In particular, I assumed (and I guess rightly so) that there would be a lack of representation of Igbo within that axis and I wanted to know what your considerations would be in that regard. By representation, I don't quite mean the existence of a surviving Igboid lect (though that would be cool and lend significant support to your speculation). Rather, my thoughts were along the lines of at least the existence of a language (or set of languages) in the Edo-Ondo borderlands that is notably lexically close to (at least) Ekpeye. Of course, perhaps not something mutually intelligible, but enough to pique interest. My reasoning is due to the fact that we still witness a high degree of language diversity within that borderland axis. It's high enough that it seems plausible to suspect that the area never experienced language invasion. There is even evidence for that in the spatial distribution of Yoruba/Igala and Edo. We can clearly see the Yoruba/Igala distribution curve around the Edo-Ondo borderlands, indicating the Akokoid family and Akpes, etc. had likely already been settled and existing in that space. This has been my thought process while giving consideration to the Edo-Ondo borderlands postulation. Now back to my response. The statistics you mentioned in bold triggered some thoughts in my mind, which I believe is more in line with your statement on how you reconciled these considerations. Let me list out my considerations so that my thought process will hopefully be clear. Basic Assumption/Proposition Contrary to the currently orthodox opinion of a southward push for Igboid languages, we propose instead an eastward push. In other words, rather than Igbo-speaking communities entering what is now "Igboland" from up north, we suggest instead that they entered from the west (or more predominantly from the south/southwest). Some Considerations 1. If we look at the spatial distribution of all the YEAI branches, we can conceive of a relatively hard line between Edoid and Igboid language communities. This suggests Igboid language communities moved into that area of the forest before them (having branched off earlier in history). 2. At a casual glance, this spatial distribution gives [me] the impression that there are no remnants of the proto-Igbo branch outside the Igbo-speaking region. In fact, considering the population and spatial distribution, it almost seems as though the entirety of proto-Igbo shifted en masse and remained largely disconnected from the rest of YEAI for quite a long time. There aren't even any notable pockets of highly related Igboid languages sprinkled between the Edo-Ondo borderlands and the western/southwest border of Igbo-speaking communities. 3. However, it is precisely because of the consideration in #2 that this current #3 consideration is particularly interesting. Despite the separation in time and space, Igbo and Akoko have maintained a higher degree of lexical similarity than Akoko and Edo. Speculative Conclusion Let me paint a picture of population movements. Relatively dense populations typically force incoming communities to settle around them as opposed to settling through them (i.e. overrun them). A survey of the current spatial distribution suggest that such is the case with both Yoruba/Igala and Edo. Yoruba could seemingly (freely) expand westward, but was seemingly not able to effectively push eastward. Edo could effectively not push eastward or westward, and so was forced to push southward. In both cases, Yoruba/Igala and Edo were forced to settle around the Akokoid and Igboid families respectively. This seems highly plausible, and it suggests that the expansion of the Yoruboid and Edoid languages would have to have been after the Akokoid. Indeed, referencing the works of Elugbe and Adetugbo (among others), we can see some credence to this. Elugbe's conclusion for the linguistic homeland of Edoid puts us straight on a path to the Ondo-Edo borderlands. Incidentally, it shows a general southern push (or more so southern than eastern). Adetugbo's work points just slightly northward from the Edo-Ondo borderlands. Incidentally, it also shows that the Yoruboid dispersal from that area was forced to wrap around the Akokoid region. It may very well be the case that Edoid and Yoruboid branched around the same time. In other words, they branched from YEAI later than Akokoid and Igboid. I'm certain you recall our discussion (also here in NL) years back regarding sound and lexical shifts with respect to proto-Igbo and the rest of YEAI. The general trend seemed to be that descendents if earlier branches maintained more recognizable features of the ancestor languages. It stands to reason that more recognizable features of ancestor languages would contribute to higher cognate scores (i.e. Akokoid and Igboid). That accounts for separation in time. To account for separation in space, it might just be as simple as you stated it. The Igboid family branched off so early that the continued expansion in time created less population density; enough for Edoid to later expand eastward and southward. This can account for separation in space. Since we know that all the YEAI branches are related, and we see the homelands of all but Igbo around Ondo, it would make sense to look away from the Niger-Benue confluence and more towards Ondo for the earliest branching of proto-Igbo speakers. This is actually insane (as in wonderfully bursting my head). This actually makes far more sense to me than the theory of shooting into the (almost dead center) of what is now "Igboland" and then both radiating outward and simultaneously pushing south from there. Perhaps this is already a lot in one post. I will come back later to give my thoughts on the Lower Cross aspect of all of this. If anything, the idea of early Lower Cross interactions coupled with the fact that Ekpeye is to the south are the main pillars of this current "Southern Entry" hypothesis. |